Social Media was created as an educational and informational resource for American Citizens. Nonetheless, it has become a tool for AI bots and tech companies to predict our next moves by manipulating our minds on social media apps. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act helped create the modern internet we use today. However, it was initially a 1996 law that regulated online pornography. Specifically, Section 230 provides legal immunity from liability for internet services and users for content posted online. Tech companies do not just want to advertise to social media users but instead want to predict a user’s next move. The process of these manipulative tactics used by social media apps has wreaked havoc on the human psyche and destroyed the social aspects of life by keeping people glued to a screen so big tech companies can profit off of it.

Social media has changed a generation for the worse, causing depression and sometimes suicide, as tech designers manipulate social media users for profit. Social media companies for decades have been shielded from legal consequences for what happens on their platforms. However, due to recent studies and court cases, this may be able to change and allow for big tech social media companies to be held accountable. A former Facebook employee, France Haugen, a whistleblower to the Senate, stated not to trust Facebook as they knowingly pushed products that harm children and young adults to further profits, which Section 230 cannot sufficiently protect. Haugen further states that researchers at Instagram (a Facebook-owned Social Media App) knew their app was worsening teenagers’ body images and mental health, even as the company publicly downplayed these effects.

There is a California Bill, Social Media Platform Duty to Children Act, that aims to make tech firms liable for Social media Addiction in children; this would allow parents and guardians to use platforms that they believe addicted children in their care through advertising, push notifications and design features that promote compulsive use, particularly the continual consumption of harmful content on issues such as eating disorders and suicide. This bill would hold companies accountable regardless of whether they deliberately designed their products to be addictive.

Social Media addiction is a psychological, behavioral dependence on social media platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, TikTok, bereal, etc. Mental Disorders are defined as conditions that affect ones thinking, feeling, mood, and behaviors. Since the era of social media, especially from 2010 on, doctors and physicians have had a hard time diagnosing patients with social media addiction and mental disorders since they seem to go hand in hand. Social Media addiction has been seen to improve mood and boost health promotions with ads. However, at the same time, it can increase the negative aspects of activities that the youth (ages 13-21) take part in. Generation Z (“Zoomers”) are people born in the late 1990s to 2010s with an increased risk of social media addiction, which has been linked to depression.

A study measured the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (“DEES”) and Experiences in Close Relationships (“ECR”) to characterize the addictive potential that social media communication applications have based on their measure of the brain. The first measure in the study was a six-item short scale consisting of DEES that was a 36-item, six-factor self-report measure of difficulties, assessing

- awareness of emotional responses,

- lack of clarity of emotional reactions,

- non-acceptance of emotional responses,

- limited access to emotion regulation strategies perceived as applicable,

- difficulties controlling impulses when experiencing negative emotions, and

- problems engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing negative emotions.

The second measure is ECR-SV which includes a twelve-item test evaluating adult attachment. The scale comprised two six-item subscales: anxiety and avoidance. Each item was rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree, which is another measure of depression, anxiety, and mania were DSM-5. The results depict that scoring at least five of the nine items on the depression scale during the same two-week period classified depression. Scoring at least three of the six symptoms on the anxiety scale was to sort anxiety. Scoring at least three of the seven traits in the mania scale has classified mania.

The objectives of these studies were to clarify that there is a high prevalence of social media addiction among college students and confirms statistically that there is a positive relationship between social media addiction and mental disorders by reviewing previous studies.

The study illustrates that there are four leading causes of social media abuse: 1)The increase in depression symptoms have occurred in conjunction with the rise of smartphones since 2007, 2) Young people, especially Generation Z, spend less time connecting with friends, and they spend more time connecting with digital content. Generation Z is known for quickly losing focus at work or study because they spend much time watching other people’s lives in an age of information explosion. 3) An increase in depression is low self-esteem when they feel negative on Social Media compared to those who are more beautiful, more famous, and wealthier. Consequently, social media users might become less emotionally satisfied, making them feel socially isolated and depressed. 4) Studying pressure and increasing homework load may cause mental problems for students, therefore promoting the matching of social media addiction and psychiatric disorders.

The popularity of the internet, smartphones, and social networking sites are unequivocally a part of modern life. Nevertheless, it has contributed to the rise of depressive and suicidal symptoms in young people. Shareholders of social media apps should be more aware of the effect their advertising has on its users. Congress should regulate social media as a public policy matter to prevent harm, such as depression or suicide among young people. The best the American people can do is shine a light on the companies that exploit and abuse their users, to the public and to congress, to hold them accountable as Haugen did. There is hope for the future as the number of bills surrounding the topic of social media in conjunction with mental health effects has increased since 2020.

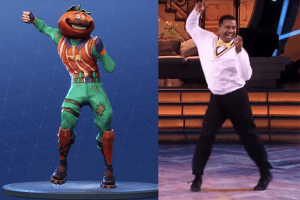

recognizes choreography as a protected form of creative expression, in order to qualify as copyrightable, the choreographic work must conform to the following elements: (1) it is an original work of authorship, (2) it is an expression as opposed to an idea, and (3) it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression. In addition, the Supreme Court has

recognizes choreography as a protected form of creative expression, in order to qualify as copyrightable, the choreographic work must conform to the following elements: (1) it is an original work of authorship, (2) it is an expression as opposed to an idea, and (3) it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression. In addition, the Supreme Court has  Office. Registration is deemed to be “made” only when “the Register has registered a copyright after examining a properly filed application.” In an attempt to salvage his claim, Mr. Ribeiro proceeded to the Office but nonetheless left emptied handed. In reviewing the application, the Office refused to grant Mr. Ribeiro a copyright because the Carlton did not rise to the level of choreography since it was a simple routine made up of just three dance steps. Likewise,

Office. Registration is deemed to be “made” only when “the Register has registered a copyright after examining a properly filed application.” In an attempt to salvage his claim, Mr. Ribeiro proceeded to the Office but nonetheless left emptied handed. In reviewing the application, the Office refused to grant Mr. Ribeiro a copyright because the Carlton did not rise to the level of choreography since it was a simple routine made up of just three dance steps. Likewise,  secured a copyright for his choreographic work. Holding that golden ticket, Hanagami argued that Epic Games did not credit or seek his consent to use, display, reproduce, sell or create derivative work based on his registered choreography.

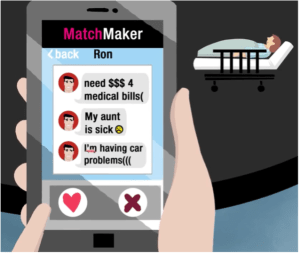

secured a copyright for his choreographic work. Holding that golden ticket, Hanagami argued that Epic Games did not credit or seek his consent to use, display, reproduce, sell or create derivative work based on his registered choreography. nd would eventually plead guilty to two federal felonies. Glenda was a victim of a Romance Scam and paid the ultimate price.

nd would eventually plead guilty to two federal felonies. Glenda was a victim of a Romance Scam and paid the ultimate price.

Prevent

Prevent