If you have spent more than 60 seconds scrolling on social media, you have undoubtably been exposed to short clips or “reels” that often reference different pop culture elements that may be protected intellectual property. While seemingly harmless, it is possible that the clips you see on various platforms are infringing on another’s copyrighted work. Oh Rats!

What Does Copyright Law Tell Us?

Copyright protection, which is codified in 17 U.S.C. §102, extends to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression”. It refers to your right, as the original creator, to make copies of, control, and reproduce your own original content. This applies to any created work that is reduced to a tangible medium. Some examples of copyrightable material include, but are not limited to, literary works, musical works, dramatic works, motion pictures, and sound recordings.

Additionally, one of the rights associated with a copyright holder is the right to make derivative works from your original work. Codified in 17 U.S.C. §101, a derivative work is “a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted. A work consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or other modifications which, as a whole, represent an original work of authorship, is a ‘derivative work’.” This means that the copyright owner of the original work also reserves the right to make derivative works. Therefore, the owner of the copyright to the original work may bring a lawsuit against someone who creates a derivative work without permission.

Derivative Works: A Recipe for Disaster!

The issue of regulating derivative works has only intensified with the growth of cyberspace and “fandoms”. A fandom is a community or subculture of fans that’s built itself up around one specific piece of pop culture and who share a mutual bond over their enthusiasm for the source material. Fandoms can also be composed of fans that actively participate and engage with the source material through creative works, which is made easier by social media. Historically, fan works have been deemed legal under the fair use doctrine, which states that some copyrighted material can be used without legal permission for the purposes of scholarship, education, parody, or news reporting, so long as the copyrighted work is only being used to the extent necessary. Fair use can also apply to a derivative work that significantly transforms the original copyrighted work, adding a new expression, meaning, or message to the original work. So, that means that “anyone can cook”, right? …Well, not exactly! The new, derivative work cannot have an economic impact on the original copyright holder. I.e., profits cannot be “diverted to the person making the derivative work”, when the revenue could or should have gone to original copyright holder.

With the increased use of “sharing” platforms, such as TikTok, Instagram, or YouTube, it has become increasingly easier to share or distribute intellectual property via monetized accounts. Specifically, due to the large amount of content that is being consumed daily on TikTok, its users are incentivized with the ability to go “viral” instantaneity, if not overnight, as well the ability to earn money through the platform’s “Creator Fund.” The Creator Fund is paid for by the TikTok ads program, and it allows creators to get paid based on the amount of views they receive. This creates a problem because now that users are getting paid for their posts, the line is blurred between what is fair use and what is a violation of copyright law. The Copyright Act fails to address the monetization of social media accounts and how that fits neatly into a fair use analysis.

Ratatouille the Musical: Anyone Can Cook?

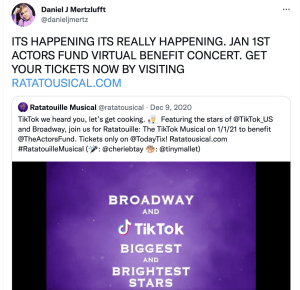

Back in 2020, TikTok users Blake Rouse and Emily Jacobson were the first of many to release songs based on Disney-Pixar’s 2007 film, Ratatouille. What started out as a fun trend for users to participate in, turned into a full-fledged viral project and eventual tangible creation. Big name Broadway stars including André De Shields, Wayne Brady, Adam Lambert, Mary Testa, Kevin Chamberlin, Priscilla Lopez, and Tituss Burgess all participated in the trend, and on December 9, 2020, it was announced that Ratatouille was coming to Broadway via a virtual benefit concert.

Premiered as a one-night livestream event in January 1 2021, all profits generated from the event were donated to the Entertainment Community Fund (formerly the Actors Fund), which is a non-profit organization that supports performers and workers in the arts and entertainment industry. It initially streamed in over 138 countries and raised over $1.5 million for the charity. Due to its success, an encore production was streamed on TikTok 10 days later, which raised an additional $500,000 for the fund (totaling $2 million). While this is unarguably a derivative work, the question of fair use was not addressed here because Disney lawyers were smart enough not to sue. In fact, they embraced the Ratatouille musical by releasing a statement to the Verge magazine:

Premiered as a one-night livestream event in January 1 2021, all profits generated from the event were donated to the Entertainment Community Fund (formerly the Actors Fund), which is a non-profit organization that supports performers and workers in the arts and entertainment industry. It initially streamed in over 138 countries and raised over $1.5 million for the charity. Due to its success, an encore production was streamed on TikTok 10 days later, which raised an additional $500,000 for the fund (totaling $2 million). While this is unarguably a derivative work, the question of fair use was not addressed here because Disney lawyers were smart enough not to sue. In fact, they embraced the Ratatouille musical by releasing a statement to the Verge magazine:

“Although we do not have development plans for the title, we love when our fans engage with Disney stories. We applaud and thank all of the online theatre makers for helping to benefit The Actors Fund in this unprecedented time of need.”

Normally, Disney is EXTREMELY strict and protective over their intellectual property. However, this small change of heart has now opened a door for other TikTok creators and fandom members to create unauthorized derivative works based on others’ copyrighted material.

Too Many Cooks in the Kitchen!

Take the “Unofficial Bridgerton Musical”, for example. In July of 2022, Netflix sued content creators Abigail Barlow and Emily Bear for their unauthorized use of Netflix’s original series, Bridgerton. The Bridgerton Series on Netflix is based on the Bridgerton book series by Julia Quinn. Back in 2020, Barlow and Bear began writing and uploading songs based on the Bridgerton series to TikTok for fun. Needless to say, the videos went viral, thus prompting Barlow and Bear to release an entire musical soundtrack based on Bridgerton. They even went so far as to win the 2022 Grammy Award for Best Musical Album.

On July 26, Barlow and Bear staged a sold-out performance with tickets ranging from $29-$149 at the New York Kennedy Center, and also incorporated merchandise for sale that included the “Bridgerton” trademark. Netflix then sued, demanding an end to these for-profit performances. Interestingly enough, Netflix was allegedly initially on board with Barlow and Bear’s project. However, although Barlow and Bear’s conduct began on social media, the complaint alleges they “stretched fanfiction way past its breaking point”. According to the complaint, Netflix “offered Barlow & Bear a license that would allow them to proceed with their scheduled live performances at the Kennedy Center and Royal Albert Hall, continue distributing their album, and perform their Bridgerton-inspired songs live as part of larger programs going forward,” which Barlow and Bear refused. Netflix also alleged that the musical interfered with its own derivative work, the “Bridgerton Experience,” an in-person pop-up event that has been offered in several cities.

Unlike the Ratatouille: The Musical, which was created to raise money for a non-profit organization that benefited actors during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Unofficial Bridgerton Musical helped line the pockets of its creators, Barlow and Bear, in an effort to build an international brand for themselves. Netflix ended up privately settling the lawsuit in September of 2022.

Has the Aftermath Left a Bad Taste in IP Holder’s Mouths?

The stage has been set, and courts have yet to determine exactly how fan-made derivative works play out in a fair use analysis. New technologies only exacerbate this issue with the monetization of social media accounts and “viral” trends. At a certain point, no matter how much you want to root for the “little guy”, you have to admit when they’ve gone too far. Average “fan art” does not go so far as to derive significant profits off the original work and it is very rare that a large company will take legal action against a small content creator unless the infringement is so blatant and explicit, there is no other choice. IP law exists to protect and enforce the rights of the creators and owners that have worked hard to secure their rights. Allowing content creators to infringe in the name of “fair use” poses a dangerous threat to intellectual property law and those it serves to protect.

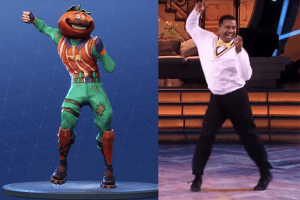

recognizes choreography as a protected form of creative expression, in order to qualify as copyrightable, the choreographic work must conform to the following elements: (1) it is an original work of authorship, (2) it is an expression as opposed to an idea, and (3) it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression. In addition, the Supreme Court has

recognizes choreography as a protected form of creative expression, in order to qualify as copyrightable, the choreographic work must conform to the following elements: (1) it is an original work of authorship, (2) it is an expression as opposed to an idea, and (3) it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression. In addition, the Supreme Court has  Office. Registration is deemed to be “made” only when “the Register has registered a copyright after examining a properly filed application.” In an attempt to salvage his claim, Mr. Ribeiro proceeded to the Office but nonetheless left emptied handed. In reviewing the application, the Office refused to grant Mr. Ribeiro a copyright because the Carlton did not rise to the level of choreography since it was a simple routine made up of just three dance steps. Likewise,

Office. Registration is deemed to be “made” only when “the Register has registered a copyright after examining a properly filed application.” In an attempt to salvage his claim, Mr. Ribeiro proceeded to the Office but nonetheless left emptied handed. In reviewing the application, the Office refused to grant Mr. Ribeiro a copyright because the Carlton did not rise to the level of choreography since it was a simple routine made up of just three dance steps. Likewise,  secured a copyright for his choreographic work. Holding that golden ticket, Hanagami argued that Epic Games did not credit or seek his consent to use, display, reproduce, sell or create derivative work based on his registered choreography.

secured a copyright for his choreographic work. Holding that golden ticket, Hanagami argued that Epic Games did not credit or seek his consent to use, display, reproduce, sell or create derivative work based on his registered choreography.