Opening

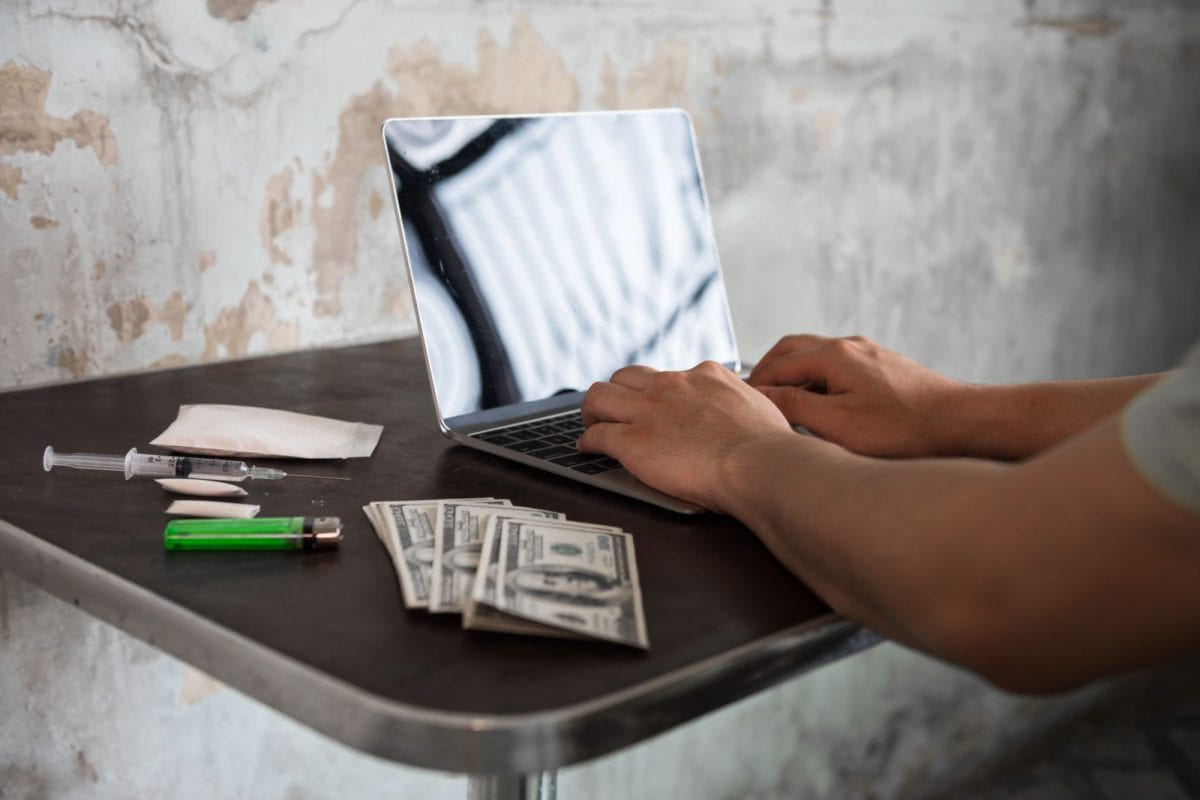

For better or worse, social media has changed our society forever. We all see and experience its impact in our daily lives, no matter the national, cultural, or social context. Nowhere is this more true than in the realm of commerce. Social media has proven to be an incredibly effective tool for the creation and maintenance of business, arguably making massive inroads into the world of marketing and sales. Above all, those with even a drop of entrepreneurial spirit no longer need to rely solely upon external investment and institutional gatekeepers to get their product out to the masses; they only need an internet connection, a device, and a willingness to build a social media presence. However, social media marketing has also enabled the growth of unethical and illegal business, including the world of illicit and gray-market drug sales.

After 40 years of the War on Drugs, many experts, commentators, and members of law enforcement argue that the illegal drug trade is alive and well. We need only to look at the evidence: drug overdoses in the US are rising, organized crime has more power than ever, and transnational shipments are becoming more common. Furthermore, the drugs being traded are becoming stronger and more dangerous. Many countries are therefore forced to search for alternative legal solutions to this crisis. For example, a growing number of jurisdictions, domestically and internationally, are (rightfully) decriminalizing or even legalizing the production and sale of cannabis. Some are pursuing the decriminalization of possession for all drugs in an effort to combat the resulting health, economic, and social equity crises from criminalization policies.

Regardless of what you think of these various policies, we cannot ignore how social media has impacted and accelerated the sale of illegal and gray-market drugs. Therefore, it behooves us to understand how dealers and companies are marketing on social media, what law is relevant in the US, and what social media companies and policy makers are doing to deal with these challenges if we are to even begin to search for solutions for this complex problem.

Examples of Marketing

The most common form of illegal drug marketing on social media is achieved by the use of timed stories functions on major image-oriented sites (e.g. Snapchat, Instagram) or by quickly posting and manually removing the advertisement (e.g. Facebook, Twitter). Essentially, the dealer posts the advertisement, sometimes showing off the product, and lists other relevant information. Once the time period expires, the post is removed and dealers feel as if they have protected their anonymity. On top of this, dealers may use emojis, other text symbols, or slang as a code to communicate the nature or type of product. These methods are used for all kinds of illegal drugs, from fentanyl to MDMA to cocaine. After that, customers usually reach out to the dealer directly. Some use the direct messaging systems of the relevant social media services. Others reach out to the dealer on a wide range of messaging applications, especially those that market privacy and security (WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, etc).

For gray-market drug sales, we must turn to the major example of THC isomer products. Δ-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the main psychoactive substance found in cannabis. It is a Schedule 1 controlled substance under US federal law banned in about half of the States. However, creative chemists and growers in cannabis-legal states have engineered a wide range of alternative isomer products, meaning products that are chemically different from the traditional THC understood by the law. While many of them are naturally occurring, their deliberate concentration essentially creates the same desired effect for users as traditional cannabis. Due to legal confusion and inaction, and alongside real world advertising and product availability, social media companies have shown that they are quite comfortable with running advertisements for such products from formal companies and letting individuals post about them.

The Law

When it comes to illegal drug dealing, the law is, as one would hope, unfavorable towards the social media companies. Most importantly, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (Title V of the Telecommunications Act of 1996) does not help them at all. Specifically, 47 USC §§ 230(e)(1) and (3) clearly delineate that federal criminal law and state laws (including state criminal law) are not impacted in any way when it comes to enforcement against them. Therefore, the § 230(c) Good Samaritan provisions, which protect social media companies from legal liability for the posts of their users so long as they actively remove them, is not relevant.

The main law of concern for these companies is the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 which, along with various amendments and international treaties, regulates the production and sale of illegal drugs at the federal level. The most relevant part is 21 USC § 843(c), which makes it illegal for anyone to advertise illegal drugs, including on the internet. While the liability balance between the user and the social media service is unclear in both statutory and case law, the lack of Section 230 protection makes these companies uneasy.

For the issue of gray-market THC isomers, the main problem is that a loophole exists in federal law via the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018. This omnibus bill, among other things, descheduled low Δ-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol cannabis, also known as hemp, from the Controlled Substances Act. While the goal was to introduce it back into farming as a useful industrial crop, the vagueness and broadness of the bill here accidentally legalized Δ-8-Tetrahydrocannabinol cannabis, another psychoactive THC isomer that can be found in hemp, and a wide range of other isomers. This fluke arguably has opened up the floodgates on these products, in the forms of vapes, edibles, tincture drops, and smokeable flower. At the federal level, the DEA has failed to address this issue under the Federal Analogue Act. Specifically, 21 USC § 802(32) defines what analogues, including isomers, are and how they can be regulated under the Controlled Substances Act. States are trying to keep up with all the isomers but clearly fighting a losing battle; just go to your local gas station or convenience store and you will find a wide array of these items available.

Role of Social Media Companies and Policy Makers

Due to the fact that the law is quite underdeveloped and scattered surrounding illegal drug advertising in the US, many social media companies have attempted to moderate such content on their own accord. The major platforms all have policies that ban the sale, display, or solicitation of illegal drugs in one form or another (Facebook/Meta, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, Snapchat). Nevertheless, this self-regulation has arguably failed.

However, the companies are not the only ones with a share of the blame for this problem; Congress needs to act by passing new statutes that force the companies to regulate and report the marketing of illegal drugs. Surprisingly, a handful of bills have been proposed to alleviate this legal quandary. Senator Marshall’s “Cooper Davis Act” (S.4858) aims to amend the Controlled Substances Act by obliging all social media companies to report any attempt to market or sell illegal drugs to the DEA within a certain time frame. This would include all user data, history, and anything else deemed relevant by investigators. Representative Wasserman Schultz is currently drafting the “Let Parents Choose Protection Act” (aka Sammy’s Law), which would force social media companies to allow parents to track the social media activity of their kids, including their interaction with drug dealers or posts about illegal drugs. These laws, among many others, raise significant and obvious concerns about privacy and free speech rights. These need to be taken seriously and included in any such bill going forward.

On the issue of the gray market for THC isomers, social media companies and Congress must also act. While I am an advocate for the federal legalization of cannabis, allowing an unregulated market to exist is quite reckless. On top of the fact that the effects of the various isomers are not well known and not regulated by the FDA, their advertising, in person and online, as a cure-all snake oil is unethical and unjustifiable. All of the major social media platforms have advertiser and business policies against unethical practices such as false advertising but fail to use them. Congress, on the other hand, has not introduced any bills in this specific area. Likewise, state lawmakers are not exempt from acting here. They need to pursue policies to regulate this gray-market in their jurisdictions to fill in the shortcomings of Congress, as New York and Kentucky are attempting to do.

Overall, the impact of social media marketing at-large must be taken seriously by the federal and state governments. While it brings about some good in spurring business, the current paradigm enables bad actors to sell seriously dangerous illegal drugs and irresponsible businessmen to push unregulated, untested, and poorly understood gray-market drugs with little to no serious oversight. Can we, as a society, change for the better? Or will we be beholden to an unsustainable status quo of techno-anarchy that will cause unnecessary and preventable harm and suffering? Only time will tell.