Have you ever found yourself stuck in an endless loop of viewing social media posts as time flies by? It’s likely. On average, people spend about 2 hours and 24 minutes on social media daily, that is 144 minutes. It is time for users to take back control of their daily lives. But how? Well, Ethan Zuckerman is at the forefront of empowering users to control their social media algorithms.

Unfollow Everything 2.0

When users of Facebook friend request another person upon being accepted, they automatically “follow” the person. This means they will see all their posts on their Home Page. Following every page, friend, or group you are involved with is what creates the infinite loop of posts users get sucked into. Right now, there is no extension or tool that gives users the ability to combat infinite scrolling on social media platforms.

Ethan Zuckerman is in the process of creating a browser extension that lets Facebook users unfollow all of their friends, groups, and pages with the click of a button.

Here’s how it works: When a user activates the browser extension, Unfollow Everything 2.0 causes the user’s browser to retrieve their list of friends, groups, and pages from Facebook. The tool would then comb through the “followed” list, causing the browser to ask Facebook to unfollow each friend, group, or page on the users list. The tool would allow the user to select friends, groups, and pages to refollow or gives the option keep their newsfeed blank and view only content that they seek out. It would also encrypt the user’s “followed“ list and save it locally on the user’s device, which would allow the user to keep the list private while still being able to automatically reverse the unfollowing process. By unfollowing everything, users can eliminate their entire News Feed. This leaves them free to use Facebook without the feed or to more actively curate it by refollowing only those friends and groups whose posts they really want to see.

Note that this isn’t the same as unfriending. By unfollowing their friends, groups, and pages, users remain connected to them and can look up their profiles at their convenience.

Tools like Unfollow Everything 2.0 can help users have better and safer online experiences by allowing them to gain control of their feeds without the involvement of government regulation.

Unfollow Everything 1.0

The original version of the tool ” Unfollow Everything 1.0” was created by British developer Louis Barclay in 2021. Barclay believed that unfollowing everything but remaining friends with everyone on the app and staying in all the user-joined groups forced users to use Facebook deliberately rather than as an endless time-suck.“I still remember the feeling of unfollowing everything for the first time. It was near-miraculous. I had lost nothing, since I could still see my favorite friends and groups by going to them directly. But I had gained a staggering amount of control. I was no longer tempted to scroll down an infinite feed of content. The time I spent on Facebook decreased dramatically. Overnight, my Facebook addiction became manageable.”

Barclay eventually received a cease and desist letter and was permanently banned from using the Facebook platform. Meta claims he violated their terms of service.

Meta’s Current Model

Currently, there is no way for users to not automatically follow every friend, page, and group on Facebook that they have liked or befriended, forcing the endless feed of posts users to see on their timelines.

Metas’ steps to unfollow everything involve manually going through each friend, group, or business and clicking the unfollow button. This task can take hours as users tend to have hundreds of connections; this is likely deterring users from going through the extensive process of regaining control over their social media algorithm.

Meta unfollow someone’s profile Directions:

- Go to that profile by typing their profile name into the search bar at the top of Facebook.

- Click at the top of their profile.

- Click Unfriend/Unfollow, then Confirm

Making a Change:

Unfollow Everything 2.0 filed a preemptive lawsuit asking the court to determine whether Facebook users’ news feeds contain objectionable material that users should be able to filter out to enjoy the platform. They argue that Unfollow Everything 2.0 is the type of tool Section 230(c)(2) intended to encourage by giving users more control over their online experiences and adequate ability to filter out content they do not want.

Zuckerman explains users currently have little to no control over how they use social media networks. “We basically get whatever controls Facebook wants. And that’s actually pretty different from how the internet has worked historically.“

Meta, in its defense against Unfollow Everything 2.0 (Ethan Zuckerman), is pushing the court to rule that a platform such as Facebook can circumvent Section 230(c)(2) through its terms of service.

Section 230

Section 230 is known for providing immunity for online computer services regarding third-party content users generate. Section 230(c)(1): “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” While Section 230(c)(1) has been a commonly litigated topic, Section 230(c)(2) however, has been rarely discussed in front of the courts.

So what is Section 230(c)(2)? Section 230(c)(2) was adopted to allow users to regulate their online experiences through technological means, including tools like Unfollow Everything 2.0. Force V. Facebook (2019) discretions that Section 230(c)(2)(B) provides immunity from claims based on actions that “enable or make available to . . . others the technical means to restrict access to” the same categories of “objectionable” material. Essentially, Section 230(c)(2)(B) empowers people to have control over their online experiences by providing immunity to the 3rd party developers of extensions/tools that users can use with social networking platforms such as Facebook.

Timeline of Litigation

May 1, 2024: Zuckerman filed a lawsuit asking the court to recognize that Section 230 protects the development of tools that empower social media users to control what they see online.

July 15, 2024: Meta filed a motion to dismiss on the lack of Zuckerman’s standing at the current time.

August 29, 2024: Zuckerman filed an opposition to Meta’s motion to dismiss.

November 7, 2024: Dismissed. However, the researcher could file at a later date because his tool was not complete at the time of the suit. Once developed, it will likely test the law.

Why social media companies do not want this:

Companies like Meta want to prevent these 3rd party extensions as much as possible because it’s in their best interest to continuously keep users engaged. Keeping users on their platform allows Meta to display more advertisements, which is their primary source of revenue. Meta’s large scale of users gives advertisers an excellent opportunity to have their message reach a broad audience. For example, in 2023, Meta generated $134 billion in revenue, 98% of which came from advertising. By making it difficult for users to control their feed adequately, Meta can make more money. If the extension of Unfollow Everything was released to the public, Meta would likely need to shift their prioritization model.

The potential future of section 230:

What’s next? In the event that the court rules in favor of Zuckerman in a future trial, giving users an expanded ability to control their social mediaitIt likely isn’t the end of the problem. Social Media Platforms have previously changed their algorithms to prevent third-party tools from being used on platforms. For example, X (then Twitter) put an end to Block Party‘s user tool by changing its API (Application Programming Interface) pricing.

Lawmakers will need to step in to fortify users’ control over their Social media algorithms. It is unreasonable to forsee the massive media conglomerates willingly giving up control that would negatively affect their ability to generate revenue.

For now, if users wish to take the initiative and control their social media usage, Android and Apple allow their consumers to regulate specific app usage in their phone settings.

r hand, supporters believe it gives a voice to marginalized groups and holds powerful people accountable in ways that traditional systems often fail to. It’s a debate about how accountability should work in a digital age—whether it’s a tool for justice or a dangerous trend that threatens free speech and fairness.

r hand, supporters believe it gives a voice to marginalized groups and holds powerful people accountable in ways that traditional systems often fail to. It’s a debate about how accountability should work in a digital age—whether it’s a tool for justice or a dangerous trend that threatens free speech and fairness.

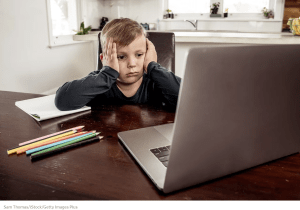

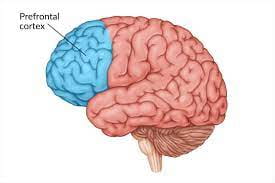

the impact this may have on their children’s brains—specifically, the effects on children’s attention span. TikTok, the prime example of short-form video content, had nearly 1.5 billion monthly active users in the

the impact this may have on their children’s brains—specifically, the effects on children’s attention span. TikTok, the prime example of short-form video content, had nearly 1.5 billion monthly active users in the

generation’s desire to avoid sustaining attention. In turn, such an influence on children can impact their ability to function in the real world.

generation’s desire to avoid sustaining attention. In turn, such an influence on children can impact their ability to function in the real world.

50% of users surveyed by TikTok said that videos lasting merely longer than a minute became

50% of users surveyed by TikTok said that videos lasting merely longer than a minute became  children. The problem is the allegations that apps such as TikTok make no effort to ensure the platform is safe for children and teens. Between the inability to monitor the content and the addictive nature discussed above, the outcome has proved catastrophic for the youth across the globe. Not only is the mental capacity of children in jeopardy, but their physical well-being faces the consequences of association with the addictive nature of short-term videos.

children. The problem is the allegations that apps such as TikTok make no effort to ensure the platform is safe for children and teens. Between the inability to monitor the content and the addictive nature discussed above, the outcome has proved catastrophic for the youth across the globe. Not only is the mental capacity of children in jeopardy, but their physical well-being faces the consequences of association with the addictive nature of short-term videos.