It is 2010. You are in middle school and your parents let your best friend come over on a Friday night. You gossip, talk about crushes, and go on all social media sites. You decide to try the latest one, Omegle. You automatically get paired with a stranger to talk to and video chat with. You speak to a few random people, and then, with the next click, a stranger’s genitalia are on your screen.

Stranger Danger

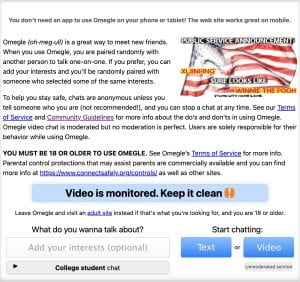

Omegle is a free video-chatting social media platform. Its primary function has become meeting new people and arranging “online sexual rendezvous.” Registration is not required. Omegle randomly pairs users for one-on-one video sessions. These sessions are anonymous, and you can skip to a new person at any time. Although there is a large warning on the home screen saying “you must be 18 or older to use Omegle”, no parental controls are available through the platform. Should you want to install any parental controls, you must use a separate commercial program.

Omegle is a free video-chatting social media platform. Its primary function has become meeting new people and arranging “online sexual rendezvous.” Registration is not required. Omegle randomly pairs users for one-on-one video sessions. These sessions are anonymous, and you can skip to a new person at any time. Although there is a large warning on the home screen saying “you must be 18 or older to use Omegle”, no parental controls are available through the platform. Should you want to install any parental controls, you must use a separate commercial program.

While the platform’s community guidelines illustrate the “dos and don’ts” of the site, it seems questionable that the platform can monitor millions of users, especially when users are not required to sign up, or to agree to any of Omegle’s terms and conditions. It, therefore, seems that this site could harbor online predators, raising quite a few issues.

One recent case surrounding Omegle involved a pre-teen who was sexually abused, harassed, and blackmailed into sending a sexual predator obscene content. In A.M. v. Omegle.com LLC, the open nature of Omegle ended up matching an 11-year-old girl with a sexual predator in his late thirties. Being easily susceptible, he forced the 11-year-old into sending pornographic images and videos of herself, perform for him and other predators, and recruit other minors. This predator was able to continue this horrific crime for three years by threatening to release these videos, pictures, and additional content publicly. The 11-year-old plaintiff sued Omegle on two general claims of platform liability through Section 230, but only one claim was able to break through the law.

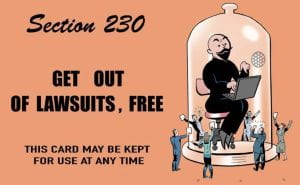

Unlimited Immunity Cards!

Under 47 U.S.C. § 230 (Section 230), social media platforms are immune from liability for content posted by third parties. As part of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, Section 230 provides almost full protection against lawsuits for social media companies since no platform is seen as a publisher or speaker of user-generated content posted on the site. Section 230 has gone so far to say that Google and Twitter were immune from liability for claims that their platforms were used to aid terrorist activities. In May of 2023, these cases moved up to the Supreme Court. Although the court declined to rule for the Google case, they ruled on the Twitter case. Google was found not liable for the claim that they stimulated the growth of ISIS through targeted recommendations and inspired an attack that killed an American student. Twitter was immune for the claim that the platform aided and abetted a terrorist group to raise funds and recruit members for a terrorist attack.

Wiping the Slate

In February of 2023, the District Court in Oregon for the Portland Division found that Section 230 immunity did not apply to Omegle in a products liability claim, and the platform was held liable for these predatory actions committed by the third party on the site. By side-stepping the third-party freedom of speech issue that comes with Section 230 immunity for an online publisher, the district court found Omegle responsible under the Plaintiff’s products liability claim, which targeted the platforms’ defective design, defective warning, negligent design, and failure to warn.

found that Section 230 immunity did not apply to Omegle in a products liability claim, and the platform was held liable for these predatory actions committed by the third party on the site. By side-stepping the third-party freedom of speech issue that comes with Section 230 immunity for an online publisher, the district court found Omegle responsible under the Plaintiff’s products liability claim, which targeted the platforms’ defective design, defective warning, negligent design, and failure to warn.

Three prongs need to be proved to preclude a platform from liability under Section 230:

- A provider of an interactive site,

- Whom is sought to be treated as a publisher or speaker, and

- For information provided by a third-party.

It is clear that Omegle is an interactive site that fits into the definition provided by Section 230. The issue then falls on the second and third prongs: if the cause of action treated Omegle as the speaker of third-party content. The sole function of randomly pairing strangers causes the foreseen danger of pairing a minor with an adult. Shown in the present case, “the function occurs before the content occurs.” By designing the platform negligently and with knowing disregard for the possibility of harm, the court ultimately concluded that the liability of the platform’s function does not pertain to third-party published content and that the claim targeted specific functions rather than users’ speech on the platform. Section 230 immunity did not apply for this first claim and Omegle was held liable.

Not MY Speech

The plaintiff’s last claim dealing with immunity under Section 230 is that Omegle negligently failed to apply reasonable precautions to provide a safe platform. There was a foreseeable risk of harm when marketing the service to children and adults and randomly pairing them. Unlike the products liability claim, the negligence claim was twofold: the function of matching people and publishing their communications to each other, both of which fall directly into Section 230’s immunity domain. The Oregon District Court drew a distinct line between the two claims, so although Omegle was not liable under Section 230 here through negligent service, they were liable through products liability.

If You Cannot Get In Through the Front Door, Try the Back Door!

For almost 30 years, social media platforms have been nearly immune from liability pertaining to Section 230 issues. In the last few years, with the growth of technology on these platforms, judges have been trying to find loopholes in the law to hold companies liable. A.M. v. Omegle has just moved through the district court level. If appealed, it will be an interesting case to follow and see if the ruling will stand or be overruled in conjunction with the other cases that have been decided.

How do you think a higher court will rule on issues like these?