Is it HIGHT TIME we allow Cannabis Content on Social Media?

The Cannabis Industry is Growing like a Weed

Social media provides a relationship between consumers and their favorite brands. Just about every company has a social media presence to advertise its products and grow its brand. Large companies command the advertising market, but smaller companies and one-person startups have their place too. The opportunity to expand your brand using social media is limitless to just about everyone. Except for the cannabis industry. With the developing struggle between social media companies and the politics of cannabis, comes an onslaught of problems facing the modern cannabis market. With recreational marijuana use legal in 21 states and Washington, D.C., and medical marijuana legal in 38 states, it may be time for this community to join the social media metaverse.

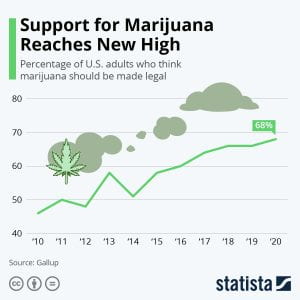

We know now that algorithms determine how many followers on a platform see a business’ content, whether or not the content is permitted, and whether the post or the user should be deleted. The legal cannabis industry has found itself in a similar struggle to legislators with social media giants ( like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) for increased transparency about their internal processes for filtering information, banning users, and moderating its platform. Mainstream cannabis businesses have been prevented from making their presence known on social media in the past, but legitimate businesses are being placed in a box with illicit drug users and prevented from advertising on public social media sites. The Legal cannabis industry is expected to be worth over $60 billion by 2024, and support for federal legalization is at an all-time high (68%). Now more than ever, brands are fighting for higher visibility amongst cannabis consumers.

Recent Legislation Could Open the Door for Cannabis

The question remains, whether the legal cannabis businesses have a place in the ever-changing landscape of the social media metaverse. Marijuana is currently a Schedule 1 narcotic on the Controlled Substances Act (1970). This categorization of Marijuana as Schedule 1 means that it has no currently accepted medical use and has a high potential for abuse. While that definition was acceptable when cannabis was placed on the DEAs list back in 1971, there has been evidence presented in opposition to that decision. Historians note, overt racism, combined with New Deal reforms and bureaucratic self-interest is often blamed for the first round of federal cannabis prohibition under the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which restricted possession to those who paid a steep tax for a limited set of medical and industrial applications. The legitimacy of cannabis businesses within the past few decades based on individual state legalization (both medical and recreational) is at the center of debate for the opportunity to market as any other business has. Legislation like the MORE act (Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement) which was passed by The House of Representatives gives companies some hope that they can one day be seen as legitimate businesses. If passed into law, Marijuana will be lowered or removed from the schedule list which would blow the hinges off the cannabis industry, legitimate businesses in states that have legalized its use are patiently waiting in the wings for this moment.

States like New York have made great strides in passing legislation to legalize marijuana the “right” way and legitimize business, while simultaneously separating themselves from the illegal and dangerous drug trade that has parasitically attached itself to this movement. The Marijuana Regulation and Tax Act (MRTA) establishes a new framework for the production and sale of cannabis, creates a new adult-use cannabis program, and expands the existing medical cannabis and cannabinoid (CBD) hemp programs. MRTA also established the Office of Cannabis Management (OCM), which is the governing body for cannabis reform and regulation, particularly for emerging businesses that wish to establish a presence in New York. The OCM also oversees the licensure, cultivation, production, distribution, sal,e and taxation of medical, adult-use, and cannabinoid hemp within New York State. This sort of regulatory body and structure are becoming commonplace in a world that was deemed to be like the “wild-west” with regulatory abandonment, and lawlessness.

But, What of the Children?

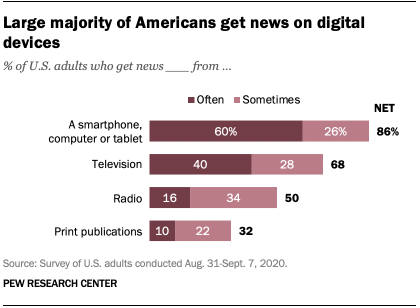

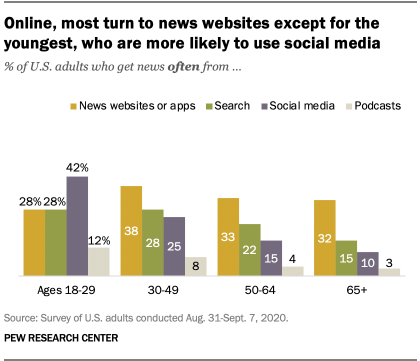

In light of all the regulation that is slowly surrounding the Cannabis businesses, will the rapidly growing social media landscape have to concede to the demands of the industry and recognize their presence? Even with regulations cannabis exposure is still an issue to many about the more impressionable members of the user pool. Children and young adults are spending more time than ever online and on social media. On average, daily screen use went up among tweens (ages 8 to 12) to five hours and 33 minutes from four hours and 44 minutes, and to eight hours and 39 minutes from seven hours and 22 minutes for teens (ages 13 to 18). This group of social media consumers is of particular concern to both the legislators and the social media companies themselves. MRTA offers protection from companies advertising with the intent of looking like common brands marketed to children. Companies are restricted to using their name and their logo, with explicit language that the item inside of the wrapper has cannabis or Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in it. MRTA restrictions along with strict community guidelines from several social media platforms and government regulations around the promotion of marijuana products, many brands are having a hard time building their communities’ presence on social media. The cannabis companies have resorted to creating their own that promote the content they are being prevented from blasting on other sites. Big-name rapper and cannabis enthusiast, Berner who created the popular edible brand “Cookies”, has been approached to partner with the creators to bolster their brand and raise awareness. Unfortunately, the sites became what mainstream social media sites feared in creating their guideline, an unsavory haven for illicit drug use and other illegal behavior. One of the pioneer apps in this field Social Club was removed from the app store after multiple reports of illegal behavior. The apps have since been more internally regulated but have not taken off like the creators intended. Legitimate cannabis businesses are still being blocked from advertising on mainstream apps.

These Companies Won’t go Down Without a Fight

While cannabis companies aren’t supposed to be allowed on social media sites, there are special rules in place if a legal cannabis business were to have a presence on a social media site. Social media is the fastest and most efficient way to advertise to a desired audience. With appropriate regulatory oversight and within the confines of the changing law, social media sites may start to feel pressure to allow more advertising from cannabis brands.

A Petition has been generated to bring META, the company that owns Facebook and Instagram among other sites, to discuss the growing frustrations and strict restrictions on their social media platforms. The petition on Change.org has managed to amass 13,000 signatures. Arden Richard, the founder of WeedTube, has been outspoken about the issues saying “This systematic change won’t come without a fight. Instagram has already begun deleting posts and accounts just for sharing the petition,”. He also stated, “The cannabis industry and community need to come together now for these changes and solutions to happen,”. If not, he fears, “we will be delivering this industry into the hands of mainstream corporations when federal legalization happens.”

Social media companies recognize the magnitude of the legal cannabis community because they have been banning its content nonstop since its inception. However, the changing landscape of the cannabis industry has made their decision to ban their content more difficult. Until federal regulation changes, businesses operating in states that have legalized cannabis will be force banned by the largest advertising platforms in the world.

The Court’s lesson from Mahanoy might be that regulations on student speech raises serious First Amendment concerns; school offi¬cials should proceed cautiously before venturing into this territory. That same caution may be prudent for both the private sector and public sector employers. Social media’s impact is not limited to situations where a person’s post impacts their employment. One example, among many, is

The Court’s lesson from Mahanoy might be that regulations on student speech raises serious First Amendment concerns; school offi¬cials should proceed cautiously before venturing into this territory. That same caution may be prudent for both the private sector and public sector employers. Social media’s impact is not limited to situations where a person’s post impacts their employment. One example, among many, is