Opening

For anyone who is chronically online as yours truly, in one way or another we have seen our favorite social media influencers, artists, commentators, and content creators complain about their problems with the current US Intellectual Property (IP) system. Be it that their posts are deleted without explanation or portions of their video files are muted, the combination of factors leading to copyright issues on social media is endless. This, in turn, has a markedly negative impact on free and fair expression on the internet, especially within the context of our contemporary online culture. For better or worse, interaction in society today is intertwined with the services of social media sites. Conflict arises when the interests of copyright holders clash with this reality. They are empowered by byzantine and unrealistic laws that hamper our ability to exist as freely as we do in real life. While they do have legitimate and fundamental rights that need to be protected, such rights must be balanced out with desperately needed reform. People’s interaction with society and culture must not be hampered, for that is one of the many foundations of a healthy and thriving society. To understand this, I venture to analyze the current legal infrastructure we find ourselves in.

Current Relevant Law

The current controlling laws for copyright issues on social media are the Copyright Act of 1976 and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). The DMCA is most relevant to our analysis; it gives copyright holders relatively unrestrained power to demand removal of their property from the internet and to punish those using illegal methods to get ahold of their property. This broad law, of course, impacted social media sites. Title II of the law added 17 U.S. Code § 512 to the Copyright Act of 1976, creating several safe harbor provisions for online service providers (OSP), such as social media sites, when hosting content posted by third parties. The most relevant of these safe harbors to this issue is 17 U.S. Code § 512(c), which states that an OSP cannot be liable for monetary damages if it meets several requirements and provides a copyright holder a quick and easy way to claim their property. The mechanism, known as a “notice and takedown” procedure, varies by social media service and is outlined in their terms and conditions of service (YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, Facebook/Meta). Regardless, they all have a complaint form or application that follows the rules of the DMCA and usually will rapidly strike objectionable social media posts by users. 17 U.S. Code § 512(g) does provide the user some leeway with an appeal process and § 512(f) imposes liability to those who send unjustifiable takedowns. Nevertheless, a perfect balance of rights is not achieved.

The doctrine of fair use, codified as 17 U.S. Code § 107 via the Copyright Act of 1976, also plays a massive role here. It established a legal pathway for the use of copyrighted material for “purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research” without having to acquire right to said IP from the owner. This legal safety valve has been a blessing for social media users, especially with recent victories like Hosseinzadeh v. Klein, which protected reaction content from DMCA takedowns. Cases like Lenz v. Universal Music Corp further established that fair use must be considered by copyright holders when preparing for takedowns. Nevertheless, failure to consider said rights by true copyright holders still happens, as sites are quick to react to DMCA complaints. Furthermore, the flawed reporting systems of social media sites lead to abuse by unscrupulous actors faking true ownership. On top of that, such legal actions can be psychologically and financially intimidating, especially when facing off with a major IP holder, adding to the unbalanced power dynamic between the holder and the poster.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996, which focuses primarily on cellular and landline carriers, is also particularly relevant to social media companies in this conflict. At the time of its passing, the internet was still in its infancy. Thus, it does not incorporate an understanding of the current cultural paradigm we find ourselves in. Specifically, the contentious Section 230 of the Communication Decency Act (Title V of the 1996 Act) works against social media companies in this instance, incorporating a broad and draconian rule on copyright infringement. 47 U.S. Code § 230(e)(2) states in no uncertain terms that “nothing in this section shall be construed to limit or expand any law pertaining to intellectual property.” This has been interpreted and restated in Perfect 10, Inc. v. CCBill LLC to mean that such companies are liable for user copyright infringement. This gap in the protective armor of Section 230 is a great concern to such companies, therefore they react strongly to such issues.

What is To Be Done?

Arguably, fixing the issues around copyright on social media is far beyond the capacity of current legal mechanisms. With ostensibly billions of posts each day on various sites, regulation by copyright holders and sites is far beyond reason. It will take serious reform in the socio-cultural, technological, and legal arenas before a true balance of liberty and justice can be established. Perhaps we can start with an understanding by copyright holders not to overreact when their property is posted online. Popularity is key to success in business, so shouldn’t you value the free marketing that comes with your copyrighted property getting shared honestly within the cultural sphere of social media? Social media sites can also expand their DMCA case management teams or create tools for users to accredit and even share revenue with, if they are an influencer or content creator, the copyright holder. Finally, congressional action is desperately needed as we have entered a new era that requires new laws. That being said, achieving a balance between the free exchange of ideas and creations and the rights of copyright holders must be the cornerstone of the government’s approach to socio-cultural expression on social media. That is the only way we can progress as an ever more online society.

Image: Freepik.com

https://www.freepik.com/free-vector/flat-design-intellectual-property-concept-with-woman-laptop_10491685.htm#query=intellectual%20property&position=2&from_view=keyword”>Image by pikisuperstar

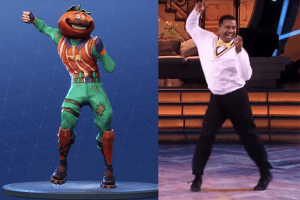

recognizes choreography as a protected form of creative expression, in order to qualify as copyrightable, the choreographic work must conform to the following elements: (1) it is an original work of authorship, (2) it is an expression as opposed to an idea, and (3) it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression. In addition, the Supreme Court has

recognizes choreography as a protected form of creative expression, in order to qualify as copyrightable, the choreographic work must conform to the following elements: (1) it is an original work of authorship, (2) it is an expression as opposed to an idea, and (3) it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression. In addition, the Supreme Court has  Office. Registration is deemed to be “made” only when “the Register has registered a copyright after examining a properly filed application.” In an attempt to salvage his claim, Mr. Ribeiro proceeded to the Office but nonetheless left emptied handed. In reviewing the application, the Office refused to grant Mr. Ribeiro a copyright because the Carlton did not rise to the level of choreography since it was a simple routine made up of just three dance steps. Likewise,

Office. Registration is deemed to be “made” only when “the Register has registered a copyright after examining a properly filed application.” In an attempt to salvage his claim, Mr. Ribeiro proceeded to the Office but nonetheless left emptied handed. In reviewing the application, the Office refused to grant Mr. Ribeiro a copyright because the Carlton did not rise to the level of choreography since it was a simple routine made up of just three dance steps. Likewise,  secured a copyright for his choreographic work. Holding that golden ticket, Hanagami argued that Epic Games did not credit or seek his consent to use, display, reproduce, sell or create derivative work based on his registered choreography.

secured a copyright for his choreographic work. Holding that golden ticket, Hanagami argued that Epic Games did not credit or seek his consent to use, display, reproduce, sell or create derivative work based on his registered choreography.