When the tune of the “Y.M.C.A.,” by The Village People starts to play, no matter the time or place, the urge to raise your arms and dance is impossible to ignore. A wave of nostalgia and childish-like happiness quickly fills the atmosphere, and as the chorus begins, you and (almost) everyone around you begin to dance the only way you know how: throwing your arms up in the air and forming the letters, duh! But what’s not so obvious is that the “Y.M.C.A.” dance, irrespective of its wild popularity and incorporation into major television and film productions since its release in 1978, is not copyrighted. The songwriters, artists, and producers each have and continue to receive the recognition, compensation, and title they deserve for their contributions to the song itself, but the inherent choreography remains unprotected. According to the Copyright Office (“the Office”), a dance “whereby a group of people spell out letters with their arms” is simply too basic to deserve copyright recognition because no matter how distinctive it may be, it is nonetheless a commonplace movement or gesture.

CONGRESS ‘GETS DOWN’

Choreographers, since the beginning of the entertainment industry, have never received the legal protections that producers, songwriters, and artists have. Although The Copyright Act of 1976 (the “Act”) officially  recognizes choreography as a protected form of creative expression, in order to qualify as copyrightable, the choreographic work must conform to the following elements: (1) it is an original work of authorship, (2) it is an expression as opposed to an idea, and (3) it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression. In addition, the Supreme Court has held that an individual may not bring a copyright infringement suit under the Act until the individual has registered with the Office. Although choreographic works were finally recognized as worthy or deserving of copyright recognition and status, the application of copyright laws to choreography since its recognition has revealed a significant grey area for intellectual property law.

recognizes choreography as a protected form of creative expression, in order to qualify as copyrightable, the choreographic work must conform to the following elements: (1) it is an original work of authorship, (2) it is an expression as opposed to an idea, and (3) it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression. In addition, the Supreme Court has held that an individual may not bring a copyright infringement suit under the Act until the individual has registered with the Office. Although choreographic works were finally recognized as worthy or deserving of copyright recognition and status, the application of copyright laws to choreography since its recognition has revealed a significant grey area for intellectual property law.

BUT IS IT JUST A SHIMMY OR A ‘CHOREOGRAPHIC WORK’?

When assessing what qualifies as a copyrightable choreographic work, the Office acknowledges that the dividing line between what is a simple routine and what is copyrightable choreography is more of a continuum, rather than a bright line. The Office also indicated certain types of works that, from the outright, may not be copyrighted: common place movements, individual dance moves or gestures, social dances, ordinary and athletic movements, and short dance routines.

Whether a particular dance qualifies as a choreographic work, or not, ultimately rests on the Office’s assessment of the following elements collectively:

(1) rhythmic movement in a defined space

(2) compositional arrangement

(3) musical or textual accompaniment

(4) dramatic content

(5) presentation before an audience

(6) execution by skilled performers

DANCING OUR WAY TO THE COURT HOUSE

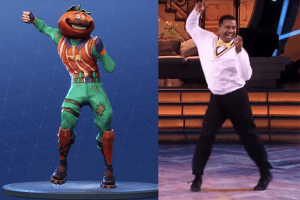

Litigation surrounding the video game Fortnite, released through Epic Games Inc., reveals just how large that grey area has grown to be. Although free to play, Fortnite’s revenue is derived from in-game purchases including purchasing a dance emote or a dance routine for the player’s avatar.

In 2019, Alfonso Ribeiro, who played the character ‘Carlton Banks’ on the TV show The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, sought justice for Epic Games’ improper use of the Carlton as a dance emote in Fortnite but was both dismissed and rejected by the court and the Office. Following the direction of the Supreme Court, the court dismissed Mr. Ribeiro’s claim for failing to register and receive final registration of his claim with the Copyright  Office. Registration is deemed to be “made” only when “the Register has registered a copyright after examining a properly filed application.” In an attempt to salvage his claim, Mr. Ribeiro proceeded to the Office but nonetheless left emptied handed. In reviewing the application, the Office refused to grant Mr. Ribeiro a copyright because the Carlton did not rise to the level of choreography since it was a simple routine made up of just three dance steps. Likewise, cases brought by rapper 2 Milly and the Backpack Kid against Epic Games alleging copyright infringement for their choreographic works the “Milly Rock,” and “the Floss” as an emote in Fortnite were also dismissed for failure to register with the Office.

Office. Registration is deemed to be “made” only when “the Register has registered a copyright after examining a properly filed application.” In an attempt to salvage his claim, Mr. Ribeiro proceeded to the Office but nonetheless left emptied handed. In reviewing the application, the Office refused to grant Mr. Ribeiro a copyright because the Carlton did not rise to the level of choreography since it was a simple routine made up of just three dance steps. Likewise, cases brought by rapper 2 Milly and the Backpack Kid against Epic Games alleging copyright infringement for their choreographic works the “Milly Rock,” and “the Floss” as an emote in Fortnite were also dismissed for failure to register with the Office.

So, since the cases were all dismissed for not having a valid registration with the Office, then having a valid registration with the Office is the golden ticket to defending your claim of improper infringement, right? Not quite.

Earlier this year in March, professional dance choreographer Kyle Hanagami (“Hanagami”) filed suit against Epic Games for using dance movements from the copyrighted routine used for the song “How Long” from Charlie Puth. Hanagami, unlike his predecessors above,  secured a copyright for his choreographic work. Holding that golden ticket, Hanagami argued that Epic Games did not credit or seek his consent to use, display, reproduce, sell or create derivative work based on his registered choreography.

secured a copyright for his choreographic work. Holding that golden ticket, Hanagami argued that Epic Games did not credit or seek his consent to use, display, reproduce, sell or create derivative work based on his registered choreography.

Regardless of the fact that Hanagami did secure his copyright before bringing a claim under the Act, the court yet again dismissed the case and agreed with Epic Games. The court stated that Hanagami’s steps are potentially protected only when combined with the other elements that make up his copyrighted work. Epic Games technically didn’t infringe on Hanagami’s copyright because the specific dance steps on their own were not entitled to copyright protection. When the works were evaluated as a whole, the court decided they were not substantially similar: “[w]hereas Hanagami’s video features human performers in a dance studio in the physical world performing for a YouTube audience, Epic Games’ work features animated characters performing for an in-game audience in a virtual world.”

And as if the grey couldn’t get any grey-er….it indeed does.

DANCING IN CIRCLES, YET AGAIN

The outcome of all this dance-litigation eludes to the central need for choreography, on its own, to be recognized and protected as a separate work. Although securing a copyright to a choreographic work will get you in the door to the courthouse, there’s no guarantee that what you’ve copyrighted will actually be protected. Thus, it is crucial that the plight of choreographers be truly recognized. Inconsistent outcomes and unclear guidelines continue to aggravate the underlying issue of allowing choreographers to pursue the copyright protection they deserve for their works. Copyrighting successful dance routines is to further help ensure dancers’ and their ability to monetize and profit from their work, but the murky waters that prevent registration and the unpredictability of outcomes in court will remain as barriers until we can clear the grey area.