Dieting, weight loss, and the need to be skinny has been prevalent in society from as early as the 19th century. People will find and try anything these days, healthy or not, to lose weight fast: diet pills, eating plans, radiofrequency lasering, you name it. People will go through such lengths to lose weight the wrong way – not exercising, not eating right, and not getting enough sleep. The emergence of social media has only compounded these issues. Social media creates pathways leading to social comparison, thin/fit ideal internalization, and self-objectification.

Type 2 diabetes is often associated with obesity and occurs when the body does not produce enough insulin, or does not react to insulin, and therefore cannot function properly. This disease is usually diagnosed in people ages 45-64 who are physically inactive and not leading a healthy lifestyle. In the early 2000s, pharmaceutical companies were looking for an easy solution to lower blood sugar to manage this disease. Enter: Ozempic.

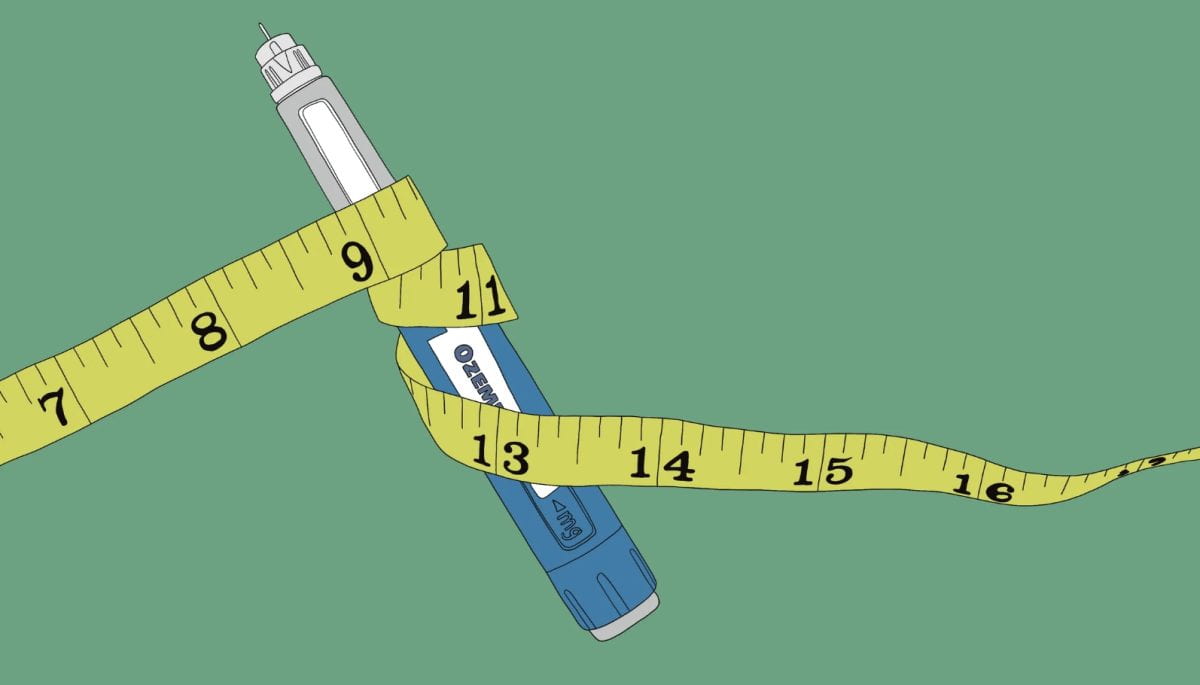

Drugmaker Novo Nordisk introduced Ozempic in 2017 when the Food and Drug Administration authorized its use for adults with type 2 diabetes. It started as a relatively mundane drug with a straightforward goal: to help individuals manage their blood sugar levels and lead healthier lives. The weekly injection was designed to simulate insulin production and suppress glucagon release, ultimately leading to a rise in hormone levels that go to your brain, telling it that the stomach is full. It also increases the time it takes for ingested food to leave the body, slowing digestion. Originally, the marketing for Ozempic only targeted adults with type 2 diabetes and was to be used with diet and exercise as a healthy way to lower blood sugar.

Turning an Unintended Outcome into a Marketing Advantage

Soon after Ozempic hit the market, surveys and studies came out that showed those who used the drug also lost weight. People who took it lost an average of 14.9% of their body weight in six months of use. The unintended weight loss from Ozempic would have usually been listed as a side effect for the medication. Now having an additional benefit of losing weight, ads for Ozempic included it along with the diabetes usage. Marketers knew their audience and this new marketing campaign attracted a large group of people who wanted to lose weight. They tapped into this market to increase sales and revenue for the drug, which continues to be very successful.

Soon after Ozempic hit the market, surveys and studies came out that showed those who used the drug also lost weight. People who took it lost an average of 14.9% of their body weight in six months of use. The unintended weight loss from Ozempic would have usually been listed as a side effect for the medication. Now having an additional benefit of losing weight, ads for Ozempic included it along with the diabetes usage. Marketers knew their audience and this new marketing campaign attracted a large group of people who wanted to lose weight. They tapped into this market to increase sales and revenue for the drug, which continues to be very successful.

In recent years, the pharmaceutical industry has witnessed a dramatic shift in how drugs are marketed, perceived, and consumed. This is largely due to the power of social media platforms and its influence on users. The allure of social media’s vast audience, the power of user-generated content, and its complex algorithms turned Ozempic into a trending topic. In the last year, social media helped Ozempic become widely known that the drug could double as a potential solution for weight loss. The drug went viral as hashtags and posts illuminated Ozempic as a cheat to losing weight, and losing weight fast. No diet or exercise needed. Individuals, not just those diagnosed with diabetes, were captivated by this prospect, and sought after Ozempic.

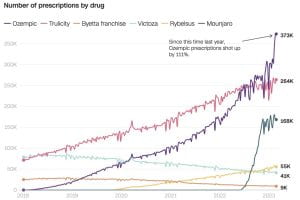

The new social media sensation garnered attention on platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube, with users, influencers, and celebrities sharing their experiences, before-and-after photos, and purported success stories. The influx of advertisements and users mentioning Ozempic increased the drug’s sales by 111% since last year. Elon Musk credited fasting, no tasty food, and Ozempic/ Wegovy (a drug very similar to Ozempic), as the reasons he shed almost 30 pounds. Other celebrities who have taken the drug, and have been vocal about it, include Amy Schumer, Chelsea Handler, Charles Barkley, Sharon Osborne, Tracy Morgan, and many more who are known to not have type 2 diabetes.

fasting, no tasty food, and Ozempic/ Wegovy (a drug very similar to Ozempic), as the reasons he shed almost 30 pounds. Other celebrities who have taken the drug, and have been vocal about it, include Amy Schumer, Chelsea Handler, Charles Barkley, Sharon Osborne, Tracy Morgan, and many more who are known to not have type 2 diabetes.

Rewards Turn to Consequences

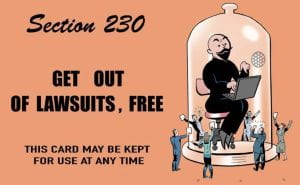

Now being marketed almost strictly as a weight loss drug from different vendors, the viral run on Ozempic has led to worldwide shortages, doctors over-prescribing the drug, and many different legal issues. The blowup of Ozempic online was at least in part fueled by people who wanted to lose weight but who did not have any medical reasons to take it. The scarcity of Ozempic, coupled with the high demand, poses a threat to the health of individuals with type 2 diabetes who depend on this medication. As a result of this issue, Novo Nordisk paused advertisements for Ozempic in May of 2023. However, most of the ads on social media were not coming from the drugmaker, and instead were coming from online pharmacies and smaller marketers. These marketers attract vulnerable users who are seeking that quick fix to weight loss. While pharmaceutical companies can be held liable if their advertisements are proven to be false and/or misleading, the social media platforms are not liable under Section 230.

Users were not walking; they were running to doctors begging for Ozempic, even users who are not overweight, let alone have diabetes. It is very easy to get a prescription for Ozempic since only an online telehealth appointment is needed. Medicines and drugs that are approved for specific uses in the United States can be prescribed off-label for any use. Off-label use is when doctors prescribe medications for purposes not approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Doctors were prescribing Ozempic for patients that did not have type 2 diabetes and did not need it. At this time, the FDA has not approved Ozempic for the sole purpose of weight loss (yet). Doctors have gotten around this by prescribing other weight loss drugs such as Wegovy. Even though off-label use is not illegal, it still raises a slew of legal issues.

Off-Label Dangers and Legal Showdowns

To this day, there have not been adequate studies of how Ozempic works for people without diabetes and there may not be enough evidence to support using the drug for people who are not diabetic. Off-label use of Ozempic can lead to serious side effects. In August of 2023, after being prescribed Ozempic for weight management, a Louisiana resident claimed to have developed gastroparesis and argued that Novo Nordisk failed in their duty to adequately warn about potential adverse side effects associated with the drug. Gastroparesis is a condition that impacts the normal movement of muscles in the stomach. Less than a month after this suit was filed, the FDA and Novo Nordisk added a warning for Ozempic that it could cause intestinal blockage. This case is still in its early stages, but more and more people are coming forward and hiring attorneys for this condition in relation to taking Ozempic. A class action or multi-district litigation is predicted to occur in these cases.

Another potential legal implication of the off-label use of Ozempic going viral is medical malpractice and the potential for mass claims against doctors and manufacturers for prescribing the weight loss drug without proper medical justification. Social media users who see advertisements on platforms and want to lose weight are not asking doctors to prescribe Ozempic to them; they are begging. The drug manufacturers aren’t providing comprehensive information to patients about potential adverse reactions and are actively promoting the use of these drugs among individuals who may receive only minimal or no long-term benefits from them.

viral is medical malpractice and the potential for mass claims against doctors and manufacturers for prescribing the weight loss drug without proper medical justification. Social media users who see advertisements on platforms and want to lose weight are not asking doctors to prescribe Ozempic to them; they are begging. The drug manufacturers aren’t providing comprehensive information to patients about potential adverse reactions and are actively promoting the use of these drugs among individuals who may receive only minimal or no long-term benefits from them.

Predicting the Future of Ozempic

To better understand the Ozempic situation, it is valuable to draw parallels with the OxyContin opioid epidemic. OxyContin was first introduced in 1996 and is a powerful narcotic designed for the management of severe pain. However, as a result of over-promotion and improper sales tactics, it was overprescribed and led to widespread abuse, addiction overdose and death. The similarities between the issues surrounding the two drugs include:

- Over-prescription– in both cases, doctors and manufacturers have played a pivotal role in the over-prescription of the medications. OxyContin was prescribed for chronic pain, a use that went beyond its intended purpose, while Ozempic was prescribed off-label for weight loss.

- Patient demand– in both cases, patient demand and pressure have played a significant role in prescription practices. Patients seeking quick and easy solutions are more likely to want and receive medications that may not be appropriate for their condition and health.

- Pharmaceutical company responsibility– Purdue Pharma, makers of OxyContin, faced, and continue to face, lawsuits for aggressively marketing the drug. Although no lawsuits have been filed against Ozempic yet for this, the responsibility of pharmaceutical companies in promoting medications beyond their FDA-approved uses could show a common thread between both drugs.

The one key difference between the OxyContin epidemic and the issues with Ozempic today is that in the early 2000s, social media sites were not as prolific. The advent of social media amplifies the speed and scale at which information, whether accurate or not, spreads. The contagious nature of user-generated content, testimonials, and before-and-after narratives on platforms has the potential to magnify the off-label promotion and demand for Ozempic as a weight loss solution. This can fuel an unwarranted surge in prescriptions without proper medical assessment, potentially leading to increased risks, adverse effects, and challenges in regulating the medication’s use. The ease with which information circulates on social media might intensify the scope and speed of the ‘Ozempic epidemic,’ raising concerns about patient safety and regulatory control.

The one key difference between the OxyContin epidemic and the issues with Ozempic today is that in the early 2000s, social media sites were not as prolific. The advent of social media amplifies the speed and scale at which information, whether accurate or not, spreads. The contagious nature of user-generated content, testimonials, and before-and-after narratives on platforms has the potential to magnify the off-label promotion and demand for Ozempic as a weight loss solution. This can fuel an unwarranted surge in prescriptions without proper medical assessment, potentially leading to increased risks, adverse effects, and challenges in regulating the medication’s use. The ease with which information circulates on social media might intensify the scope and speed of the ‘Ozempic epidemic,’ raising concerns about patient safety and regulatory control.

Where Does the Liability Land?

The story of Ozempic’s transformation from a diabetes medication to a weight loss sensation driven by social media is a compelling example of how the digital age can shape public perception and lead to a vast number of legal issues. If Section 230 is amended and sets forth certain parameters in which social media sites can be liable, could platforms be held accountable for the shortage of the drug due to social media’s contributions of Ozempic’s popularity? Could the platforms be responsible for the possible increase in body image issues and eating disorders associated with the trend to be skinny?

Omegle is a free video-chatting social media platform. Its primary function has become meeting new people and arranging “

Omegle is a free video-chatting social media platform. Its primary function has become meeting new people and arranging “

found that Section 230 immunity did not apply to Omegle in a

found that Section 230 immunity did not apply to Omegle in a