Want to lose 20 pounds in 4 days? Try this *insert any miracle weight-loss product * and you’ll be skinny in no time!

Miracle weight-loss products (MWLP) are dietary supplements that either work as an appetite suppressant or forcefully induce weight loss. These products are not approved or indicated by pharmaceutical agencies as weight loss prophylactics. Social media users are continuously bombarded with the newest weight-loss products via targeted advertisements and endorsements from their favorite influencers. Users are force fed false promises of achieving the picture-perfect body while companies are profiting off their delusions. Influencer marketing has increased significantly as social media becomes more and more prevalent. 86 percent of women use social media for purchasing advice. 70 percent of teens trust influencers more than traditional celebrities. If you’re on social media, then you’ve seen your favorite influencer endorsing some form of a MWLP and you probably thought to yourself “well if Kylie Jenner is using it, it must be legit.”

The advertisements of MWLP are promoting an unrealistic and oversexualized body image. This trend of selling skinny has detrimental consequences, often leading to body image issues, such as body dysmorphia and various eating disorders. In 2011, the Florida House Experience conducted a study among 1,000 men and women. The study revealed that 87 percent of women and 65 percent of men compare their bodies to those they see on social media. From the 1,000 subjects, 50 percent of the women and 37 percent of the men viewed their bodies unfavorably when compared to those they saw on social media. In 2019, Project Know, a nonprofit organization that studies addictive behaviors, conducted a study which suggested that social media can worsen genetic and psychological predispositions to eating disorders.

Who Is In Charge?

The collateral damages that advertisements of MWLP have on a social media user’s body image is a societal concern. As the world becomes more digital, even more creators of MWLP are going to rely on influencers to generate revenue for their products, but who is in charge of monitoring the truthfulness of these advertisements?

In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are the two federal regulators responsible for promulgating regulations relating to dietary supplements and other MWLP. While the FDA is responsible for the labeling of supplements, they lack jurisdiction over advertising. Therefore, the FTC is primarily responsible for advertisements that promote supplements and over-the-counter drugs.

The FTC regulates MWLP advertising through the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 (the Act). Sections 5 and 12 of the Act collectively prohibit “false advertising” and “deceptive acts or practices” in the marketing and sales of consumer products, and grants authority to the FTC to take action against those companies. An advertisement is in violation of the Act when it is false, misleading, or unsubstantiated. An advertisement is false or misleading when it contains “objective, material representation that is likely to deceive consumers acting reasonably under the circumstances.” An advertisement is unsubstantiated when it lacks “a reasonable basis for its contained representation.” With the rise of influencer marketing, the Act also requires influencers to clearly disclose when they have a financial or other relationship with the product they are promoting.

Under the Act, the FTC has taken action against companies that falsely advertise MWLP. The FTC typically brings enforcement claims against companies by alleging that the advertiser’s claims lack substantiation. To determine the specific level and type of substantiation required, the FTC considers what is known as the “Pfizer factors” established In re Pfizer. These factors include:

-

- The type and specificity of the claim made.

- The type of product.

- The possible consequences of a false claim.

- The degree of reliance by consumers on the claims.

- The type, and accessibility, of evidence adequate to form a reasonable basis for making the particular claims.

In 2014, the FTC applied the Pfizer factors when they brought an enforcement action seeking a permanent injunction against Sensa Products, LLC. Since 2008, Sensa sold a powder weight loss product that allegedly could make an individual lose 30 pounds in six months without dieting or exercise. The company advertised their product via print, radio, endorsements, and online ads. The FTC claimed that Sensa’s marketing techniques were false and deceptive because they lacked evidence to support their health claims, i.e., losing 30 pounds in six months. Furthermore, the FTC additionally claimed that Sensa violated the Act by failing to disclose that their endorsers were given financial incentives for their customer testimonials. Ultimately, Sensa settled, and the FTC was granted the permanent injunction.

What Else Can We Do?

Currently, the FTC, utilizing its authority under the Act, is the main legal recourse for removing these deceitful advertisements from social media. Unfortunately, social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc., cannot be liable for the post of other users. Under section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” That means, social media platforms cannot be held responsible for the misleading advertisements of MWLP; regardless of if the advertisement is through an influencer or the companies own social media page and regardless of the collateral consequences that these advertisements create.

However, there are other courses of action that social media users and social media platforms have taken to prevent these advertisements from poisoning the body images of users. Many social media influencers and celebrities have rose to the occasion to have MWLP advertisements removed. In fact, in 2018, Jameela Jamil, an actress starring on The Good Place, launched an Instagram account called I Weigh which “encourages women to feel and look beyond the flesh on their bones.” Influencer activism has led to Instagram and Facebook blocking users, under the age of 18, from viewing posts advertising certain weight loss products or other cosmetic procedures. While these are small steps in the right direction, more work certainly needs to be done.

Vernon Gebeth, the leading police homicide investigation instructor, believes time is an investigator’s worst enemy. Eighty-five percent of abducted children are killed within the first five hours. Almost all are killed within the first twenty-four hours. Time is also critical because, for each hour that passed, the distance a suspect’s vehicle can travel expands by seventy-five miles in either direction. In five hours, the area can become larger than 17,000 square miles. Like Amber Alerts, social media can be used to quickly transmit information to people across the country in time-sensitive cases.

Vernon Gebeth, the leading police homicide investigation instructor, believes time is an investigator’s worst enemy. Eighty-five percent of abducted children are killed within the first five hours. Almost all are killed within the first twenty-four hours. Time is also critical because, for each hour that passed, the distance a suspect’s vehicle can travel expands by seventy-five miles in either direction. In five hours, the area can become larger than 17,000 square miles. Like Amber Alerts, social media can be used to quickly transmit information to people across the country in time-sensitive cases.

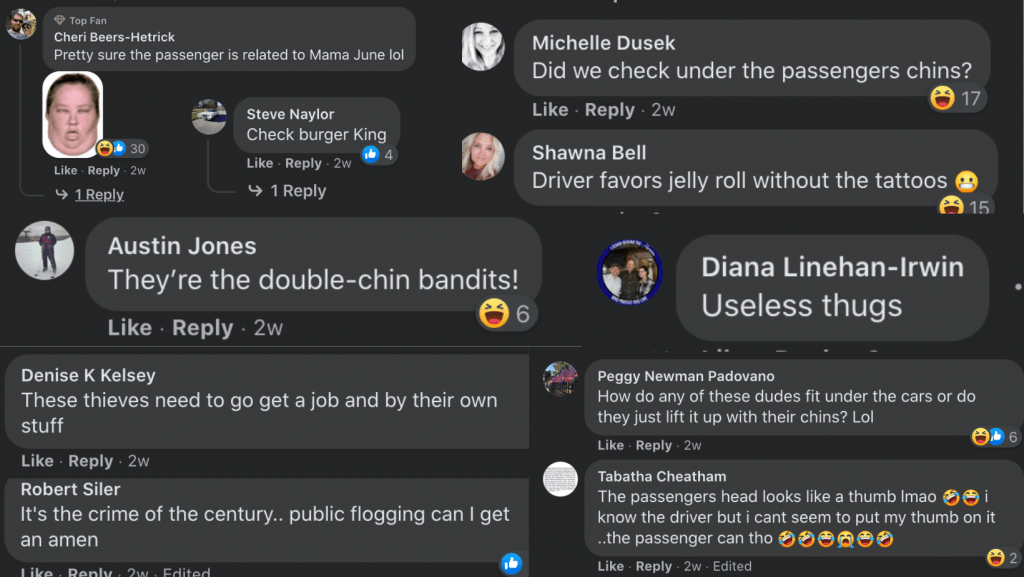

Police received a tip and located a social media posting by John E. Mogan II of himself with wads of cash in 2015. He was charged with robbing an Ashville, Ohio bank. He pled guilty and was sentenced to three years in prison. According to news reports, Morgan previously served prison time for another bank robbery.

Police received a tip and located a social media posting by John E. Mogan II of himself with wads of cash in 2015. He was charged with robbing an Ashville, Ohio bank. He pled guilty and was sentenced to three years in prison. According to news reports, Morgan previously served prison time for another bank robbery.

:focal(1435x1214:1436x1215)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/b0/ad/b0ad80d1-737e-4368-b02e-81558703cc89/istock-1151157687.jpg)