Social media regulation is a touchy subject in the United States. Congress and the White House have proposed, advocated, and voted on various bills, aimed at protecting and guarding people from data misuse and misappropriation, misinformation, harms suffered by children, and for the implications of vast data collection. Some of the most potent concerns about social media stem from use and misuse of information by the platforms- from the method of collection, to notice of collection and use of collected information. Efforts to pass a bill regulating social media have been frustrated, primarily by the First Amendment right to free speech. Congress has thus far failed to enact meaningful regulation on social media platforms.

The way forward may well be through privacy law. Privacy laws give people some right to control their own personhood including their data, right to be left alone, and how and when people see and view them. Privacy laws originated in their current form in the late 1800’s with the impetus being one’s freedom from constant surveillance by paparazzi and reporters, and the right to control your own personal information. As technology mutated, our understanding of privacy rights grew to encompass rights in our likeness, our reputation, and our data. Current US privacy laws do not directly address social media, and a struggle is currently playing between the vast data collection practices of the platforms, immunity for platforms under Section 230, and private rights of privacy for users.

There is very little Federal Privacy law, and that which does exist is narrowly tailored to specific purposes and circumstances in the form of specific bills. Somes states have enacted their own privacy law scheme, California being on the forefront, Virginia, Colorado, Connecticut, and Utah following in its footsteps. In the absence of a comprehensive Federal scheme, privacy law is often judge-made, and offers several private rights of action for a person whose right to be left alone has been invaded in some way. These are tort actions available for one person to bring against another for a violation of their right to privacy.

Privacy Law Introduction

Privacy law policy in the United States is premised on three fundamental personal rights to privacy:

- Physical right to privacy- Right to control your own information

- Privacy of decisions– such as decisions about sexuality, health, and child-rearing. These are the constitutional rights to privacy. Typically not about information, but about an act that flows from the decision

- Proprietary Privacy – the ability to protect your information from being misused by others in a proprietary sense.

Privacy Torts

Privacy law, as it concerns the individual, gives rise to four separate tort causes of action for invasion of privacy:

- Intrusion upon Seclusion- Privacy law provides a tort cause of action for intrusion upon seclusion when someone intentionally intrudes upon the reasonable expectation of seclusion of another, physically or otherwise, and the intrusion is objectively highly offensive.

- Publication of Private Facts- One gives publicity To a matter concerning the Private life of another that is not of legitimate concern to the public, and the matter publicized would be objectively highly offensive. The first amendment provides a strong defense for publication of truthful matters when they are considered newsworthy.

- False Light – One who gives publicity to a matter concerning another that places the other before the public in a false light when The false light in which the other was placed would be objectively highly offensive and the actor had knowledge of or acted in reckless disregard as to the falsity of the publicized matter and the false light in which the other would be placed.

- Appropriation of name and likeness- Appropriation of one’s name or likeness to the defendant’s own use or benefit. There is no appropriation when a persona’s picture is used to illustrate a non-commercial, newsworthy article. This is usually commercial in nature but need not be. The appropriation could be of “identity”. It need not be misappropriation of name, it could be the reputation, prestige, social or commercial standing, public interest, or other value on the plaintiff’s likeness.

These private rights of action are currently unavailable for use against social media platforms because of Section 230 of the Decency in Communications Act, which provides broad immunity to online providers for posts on their platforms. Section 230 prevents any of the privacy torts from being raised against social media platforms.

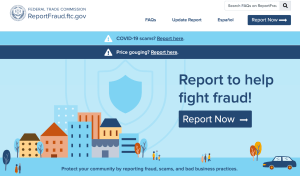

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Social Media

Privacy law can implicate social media platforms when their practices become unfair or deceptive to the public through investigation by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The FTC is the only federal agency with both consumer protection and competition jurisdiction in broad sectors of the economy. FTC investigates business practices where those practices are unfair or deceptive. FTC Act 15 U.S.C S 45- Act prohibits “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce” and grants broad jurisdiction over privacy practices of businesses to the FTC. Trade practice is unfair if it causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers which is not reasonably avoidable by consumers themselves and is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or competition. A deceptive act or practice is a material representation, omission, or practice that is likely to mislead the consumer acting reasonably in the circumstances, to the consumer’s detriment.

Critically, there is no private right of action in FTC enforcement. The FTC has no ability to enforce fines for S5 violations but can provide injunctive relief. By design, the FTC has very limited rulemaking authority, and looks to consent decrees and procedural, long-lasting relief as an ideal remedy. The FTC pursues several types of misleading or deceptive policy and practices that implicate social media platforms: notice and choice paradigms, broken promises, retroactive policy changes, inadequate notice, and inadequate security measures. Their primary objective is to negotiate a settlement where the company submits to certain measures of control of oversight by the FTC for a certain period of time. Violations of the agreements could yield additional consequences, including steep fines and vulnerability to class action lawsuits.

Relating to social media platforms, the FTC has investigated misleading terms and conditions, and violations of platform’s own policies. In Re Snapchat, the platform claimed that user’s posted information disappeared completely after a certain period of time, however, through third party apps and manipulation of user’s posts off of the platform, posts could be retained. The FTC and Snapchat settled, through a consent decree, to subject Snapchat to FTC oversight for 20 years.

The FTC has also investigated Facebook for violation of its privacy policy. Facebook has been ordered to pay a $5 billion penalty and to submit to new restrictions and a modified corporate structure that will hold the company accountable for the decisions it makes about its users’ privacy to settle FTC charges claiming that they violated a 2012 agreement with the agency.

Unfortunately, none of these measures directly give individuals more power over their own privacy. Nor do these policies and processes give individuals any right to hold platforms responsible for being misled by algorithms using their data, or for intrusion into their privacy by collecting data without allowing an opt-out.

Some of the most harmful social media practices today relate to personal privacy. Some examples include the collection of personal data, the selling and dissemination of data through the use of algorithms designed to subtly manipulate our pocketbooks and tastes, collection and use of data belonging to children, and the design of social media sites to be more addictive- all in service of the goal of commercialization of data.

No current Federal privacy scheme exists. Previous Bills on Privacy have been few and narrowly tailored to relatively specific circumstances and topics like healthcare and medical data protection by HIPPA, protection of data surrounding video rentals as in the Video Privacy Protection Act, and narrow protection for children’s data in Children’s Online Protection Act. All the schemes are outdated and fall short of meeting the immediate need of broad protection of widely collected and broadly utilized data from social media.

Current Bills on Privacy

Upon request from some of the biggest platforms, outcry from the public, and the White House’s request for Federal Privacy regulation, Congress appears poised to act. The 118th Congress has pushed privacy law as a priority in this term by introducing several bills related to social media privacy. There are at least ten Bills currently pending between the House of the Senate addressing a variety of issues and concerns from Children’s data privacy to the minimum age for use and designation of a new agency to monitor some aspects of privacy.

S744– The Data Care Act of 2023 aims to protect social media user’s data privacy by imposing fiduciary duties on the platforms. The original iteration of the bill was introduced in 2021 and failed to receive a vote. It was re-introduced in March of 2023 and is currently pending. Under the act, social media platforms would have the duty to reasonably secure user’s data from access, refrain from using the data in a way that could foreseeably “benefit the online service provider to the detriment of the end user” and to prevent disclosure of user’s data unless the party is also bound by these duties. The bill authorizes the FTC and certain state officials to take enforcement actions upon breach of those duties. The states would be permitted to take their own legal action against companies for privacy violations. The bill would also allow the FTC to intervene in the enforcement efforts by imposing fines for violations.

H.R.2701 – Perhaps the most comprehensive piece of legislation on the House floor is the Online Privacy Act. In 2023, the bill was reintroduced by democrat Anna Eshoo after an earlier version on the bill failed to receive a vote and died in Congress. The Online Privacy Act aims to protect users by providing individuals rights relating to the privacy of their personal information. The bill would also provide privacy and security requirements for treatment of personal information. To accomplish this, the bill established a new agency – the Digital Privacy Agency- which would be responsible for enforcement of the rights and requirements. The new individual rights in privacy are broad and include the rights of access, correction, deletion, human review of automated decision, individual autonomy, right to be informed, and right to impermanence, amongst others. This would be the most comprehensive plan to date. The establishment of a new agency with a task specific to administration and enforcement of privacy laws would be incredibly powerful. The creation of this agency would be valuable irrespective of whether this bill is passed.

HR 821– The Social Media Child Protection Act is a sister bill to one by a similar name which originated in the Senate. This bill aims to protect children from the harms of social media by limiting children’s access to it. Under the bill, Social Media platforms are required to verify the age of every user before accessing the platform by submitting a valid identity document or by using another reasonable verification method. A social media platform will be prohibited from allowing users under the age of 16 to access the platform. The bill also requires platforms to establish and maintain reasonable procedures to protect personal data collected from users. The bill affords for a private right of action as well as state and FTC enforcement.

S 1291–The Protecting Kids on Social Media Act is similar to its counterpart in the House, with slightly less tenacity. It similarly aims to protect children from social media’s harms. Under the bill, platforms must verify its user’s age, not allow the user to use the service unless their age has been verified, and must limit access to the platform for children under 12. The bill also prohibits retention and use of information collected during the age verification process. Platforms must take reasonable steps to require affirmative consent from the parent or guardian of a minor who is at least 13 years old for the creation of a minor account, and reasonably allow access for the parent to later revoke that consent. The bill also prohibits use of data collected from minors for algorithmic recommendations. The bill would require the Department of Commerce to establish a voluntary program for secure digital age verification for social media platforms. Enforcement would be through the FTC or state action.

S 1409– The Kids Online Safety Act, proposed by Senator Blumenthal of Connecticut, also aims to protect minors from online harms. This bill, as does the Online Safety Bill, establishes fiduciary duties for social media platforms regarding children using their sites. The bill requires that platforms act in the best interest of minors using their services, including mitigating harms that may arise from use, sweeping in online bullying and sexual exploitation. Social media sites would be required to establish and provide access to safeguards such as settings that restrict access to minor’s personal data and granting parents the tools to supervise and monitor minor’s use of the platforms. Critically, the bill establishes a duty for social media platforms to create and maintain research portals for non-commercial purposes to study the effect that corporations like the platforms have on society.

Overall, these bills indicate Congress’s creative thinking and commitment to broad privacy protection for users from social media harms. I believe the establishment of a separate body to govern, other than the FTC which lacks the powers needed to compel compliance, to be a necessary step. Recourse for violations on par with the EU’s new regulatory scheme, mainly fines in the billions, could help.

Many of the bills, for myriad aims, establish new fiduciary duties for the platforms in preventing unauthorized use and harms for children. There is real promise in this scheme- establishing duty of loyalty, diligence and care for one party has a sound basis in many areas of law and would be more easily understood in implementation.

The notion that platforms would need to be vigilant in knowing their content, studying its affects, and reporting those effects may do the most to create a stable future for social media.

The legal responsibility for platforms to police and enforce their policies and terms and conditions is another opportunity to further incentivize platforms. The FTC currently investigates policies that are misleading or unfair, sweeping in the social media sites, but there could be an opportunity to make the platforms legally responsible for enforcing their own policies, regarding age, against hate, and inappropriate content, for example.

What would you like to see considered in Privacy law innovation for social media regulation?

the impact this may have on their children’s brains—specifically, the effects on children’s attention span. TikTok, the prime example of short-form video content, had nearly 1.5 billion monthly active users in the

the impact this may have on their children’s brains—specifically, the effects on children’s attention span. TikTok, the prime example of short-form video content, had nearly 1.5 billion monthly active users in the

generation’s desire to avoid sustaining attention. In turn, such an influence on children can impact their ability to function in the real world.

generation’s desire to avoid sustaining attention. In turn, such an influence on children can impact their ability to function in the real world.

50% of users surveyed by TikTok said that videos lasting merely longer than a minute became

50% of users surveyed by TikTok said that videos lasting merely longer than a minute became  children. The problem is the allegations that apps such as TikTok make no effort to ensure the platform is safe for children and teens. Between the inability to monitor the content and the addictive nature discussed above, the outcome has proved catastrophic for the youth across the globe. Not only is the mental capacity of children in jeopardy, but their physical well-being faces the consequences of association with the addictive nature of short-term videos.

children. The problem is the allegations that apps such as TikTok make no effort to ensure the platform is safe for children and teens. Between the inability to monitor the content and the addictive nature discussed above, the outcome has proved catastrophic for the youth across the globe. Not only is the mental capacity of children in jeopardy, but their physical well-being faces the consequences of association with the addictive nature of short-term videos.

Children, however, are

Children, however, are  The sweeping transformation of social media platforms over the past several years has given rise to convenient and cost-effective advertising. Advertisers are now able to market their products or services to consumers (i.e. users) at

The sweeping transformation of social media platforms over the past several years has given rise to convenient and cost-effective advertising. Advertisers are now able to market their products or services to consumers (i.e. users) at  should

should  drink, Muse in a

drink, Muse in a

P.C. monitors in our day-to-day lives created a new opportunity for video game Developers. Slowly,

P.C. monitors in our day-to-day lives created a new opportunity for video game Developers. Slowly,  id Software, is a series that includes various FPS video games. Among the first, the Doom series introduced

id Software, is a series that includes various FPS video games. Among the first, the Doom series introduced  harass one-another too. Today, essentially all video games include some sort of communication tool. Users of most video games can usually chat, talk, or communicate with symbols or gestures with other users while also playing. Video games, however, are still socially considered games. To purchase, they are found in the video-game isle of

harass one-another too. Today, essentially all video games include some sort of communication tool. Users of most video games can usually chat, talk, or communicate with symbols or gestures with other users while also playing. Video games, however, are still socially considered games. To purchase, they are found in the video-game isle of  Amendment speech that has permitted, and continues to permit, societal issues of verbal racial discrimination and harassment to grow.

Amendment speech that has permitted, and continues to permit, societal issues of verbal racial discrimination and harassment to grow. by game developers and software creators. But rather, the plight of violent and toxic communication and its impact on society is left in the hands of the gamer itself. It’s now up to @B100DpR1NC3$$ to bring justice for @PIgSl@y3r’s potty mouth by effectively remembering to submit a complaint after he finished slaying the dragon and never knowing or remembering to check if the user was ever banned.

by game developers and software creators. But rather, the plight of violent and toxic communication and its impact on society is left in the hands of the gamer itself. It’s now up to @B100DpR1NC3$$ to bring justice for @PIgSl@y3r’s potty mouth by effectively remembering to submit a complaint after he finished slaying the dragon and never knowing or remembering to check if the user was ever banned.

exactly team-players. These teams instead rely on the leg work of in-game reports by actively-playing gamers, and artificial intelligence. As it turns out, the anti-toxicity team doesn’t even play the game. The team, as acknowledged by Activision, merely review reports that have already been submitted by game players.

exactly team-players. These teams instead rely on the leg work of in-game reports by actively-playing gamers, and artificial intelligence. As it turns out, the anti-toxicity team doesn’t even play the game. The team, as acknowledged by Activision, merely review reports that have already been submitted by game players.