As an individual that has been around, and currently living with, a call-of-dutier (i.e. one that plays Call of Duty), if I heard @yoUrD0gzM1n3 scream “S*** THAT YOU F**** N****,” over the microphone, I wouln’t flinch. The vulgar and violent communication between video game players, is not only normalized in today’s society, but vigilantly evades regulation. The video game industry, once thought of as an innocent pass-time or hobby, has since developed into a weapon for communication, and from the looks of it, it was my responsibility to hold @yoUrD0gzM1n3 accountable for his discriminatory remarks.

THE VIRTUAL SNIPER

The video game industry began on a some-what yellow brick road. Beginning in the ‘70s and well into the ‘80s, video game launches such as Space Invaders, Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, and Flight started the mark of a new era: the gamer life.

But as video games began to increase in popularity, and new technology began to emerge, the video game industry, too, was greeted with a dark upgrade. The creation, mass production, and incorporation of computers, consoles, and  P.C. monitors in our day-to-day lives created a new opportunity for video game Developers. Slowly, first person shooter (FPS), a genre of video games played from the point of view of the protagonist carrying a weapon, began to emerge.

P.C. monitors in our day-to-day lives created a new opportunity for video game Developers. Slowly, first person shooter (FPS), a genre of video games played from the point of view of the protagonist carrying a weapon, began to emerge.

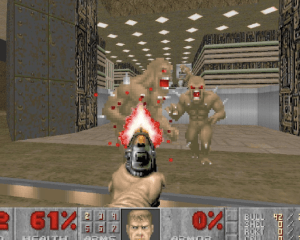

id Software, is a series that includes various FPS video games. Among the first, the Doom series introduced “3D graphics, third-dimension spatiality, networked multiplayer gameplay, and support for player-created modifications” that the gaming industry had seen at the time.

id Software, is a series that includes various FPS video games. Among the first, the Doom series introduced “3D graphics, third-dimension spatiality, networked multiplayer gameplay, and support for player-created modifications” that the gaming industry had seen at the time. BEFORE I SHOOT, LET ME SAY SOMETHING REAL QUICK

harass one-another too. Today, essentially all video games include some sort of communication tool. Users of most video games can usually chat, talk, or communicate with symbols or gestures with other users while also playing. Video games, however, are still socially considered games. To purchase, they are found in the video-game isle of Target or Best Buy, or in a video-game store like Game Stop.

harass one-another too. Today, essentially all video games include some sort of communication tool. Users of most video games can usually chat, talk, or communicate with symbols or gestures with other users while also playing. Video games, however, are still socially considered games. To purchase, they are found in the video-game isle of Target or Best Buy, or in a video-game store like Game Stop.But, despite being a game, they are considered more similar to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and are constitutionally protected as such.

@SCOTUS on ‘Live’

The Supreme Court ultimately put the nail in the coffin, and went with the latter.

In Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Ass’n (2011), video games first received constitutional protection. In Brown, the Court invalidated a California law that prohibited the sale or rental of violent video games to minors without a parent present. The Court stated:

Like the protected books, plays, and movies that preceded them, video games communicate ideas — and even social messages — through many familiar literary devices … and through features distinctive to the medium. That suffices to confer First Amendment protection.

BLIND PROTECTION

Amendment speech that has permitted, and continues to permit, societal issues of verbal racial discrimination and harassment to grow.

Amendment speech that has permitted, and continues to permit, societal issues of verbal racial discrimination and harassment to grow.Video games, although as a product are a form of expression, include certain communicative elements that shouldn’t necessarily be protected as such. What about the expression within the game, between players? Should @PIgSl@y3r’s chat to @B100DpR1NC3$$ stating “f*** y**, your mom is a b****” be considered ‘the spreading of knowledge or information’?

players are therefore at the disposal of monitoring, or not,

by game developers and software creators. But rather, the plight of violent and toxic communication and its impact on society is left in the hands of the gamer itself. It’s now up to @B100DpR1NC3$$ to bring justice for @PIgSl@y3r’s potty mouth by effectively remembering to submit a complaint after he finished slaying the dragon and never knowing or remembering to check if the user was ever banned.

by game developers and software creators. But rather, the plight of violent and toxic communication and its impact on society is left in the hands of the gamer itself. It’s now up to @B100DpR1NC3$$ to bring justice for @PIgSl@y3r’s potty mouth by effectively remembering to submit a complaint after he finished slaying the dragon and never knowing or remembering to check if the user was ever banned.JUSTICE IN THE HANDS OF @B100DpR1NC3$$

To combat overall video game toxicity (generally encompassing all in-game and game-related harassment, hate speech, discrimination, bullying, sexualization, incitement of violence, and like conduct), developers have met calls for a solution with mediocre monitoring and reporting systems. Creators across the gaming industry largely rely on in-game player reporting systems, and artificial intelligence-backed automated filtering systems to find and detect abusive players. Community standards and guidelines are posted and updated, gamer-submitted reports are reviewed, and the automated systems continue to filter. Developers have also had to curtail their video games overseas, in order to abide by International censorship guidelines. Most recently in 2009, Russia took argument with the overall terroristic portrayal of the Russians in Activision’s Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, forcing Activsion to make edits in certain versions of the game, and banning the console version as a whole.

Censorship policies, however, are ultimately upheld by users and players themselves. In order to monitor speech, developers have created varieties of reporting mechanisms in which users can report other users for harassment, discrimination, and other forms of harmful speech. Players not only have the responsibility of beating the next level and unlocking the next perk, but in order to play the game, Activsion say’s they must help out, too.

A CLOSER LOOK: ACTIVISION BLIZZARD

Activision Blizzard, Inc. the first third-party game developer (solely developing software, and not physical consoles), first emerged in 1979 and has since made a core presence in the gaming-realm. Activsion’s world renowned games, such as Candy Crush, The Call of Duty Series, and World of Warcraft (oh my!). But along with the Developer’s positive impact and developments on the industry, also came the bad. The Call of Duty Series, the  most violent of them all, has notoriously been scrutinized for its incessant depiction of violence and racism, as well as vulgar, hostile gamer-to-gamer communication. If you compare Atari’s 1980 Battlezone with Activision’s Call of Duty Series, the overall deadliness and gore depicted within the game has greatly expanded, as much as the harassment, hate speech, violence, and discrimination both portrayed and encouraged.

most violent of them all, has notoriously been scrutinized for its incessant depiction of violence and racism, as well as vulgar, hostile gamer-to-gamer communication. If you compare Atari’s 1980 Battlezone with Activision’s Call of Duty Series, the overall deadliness and gore depicted within the game has greatly expanded, as much as the harassment, hate speech, violence, and discrimination both portrayed and encouraged.

Most recently, Activision’s latest update to it’s Code of Conduct for the Call of Duty series outlines efforts in “combat[ting] toxic behavior.” Before it’s latest release of the series, Call of Duty: Warzone 2.0, Activision publicly reiterated its commitment in “delivering a positive gameplay experience.” The three key elements outlining the new code include: treat everyone with respect, compete with integrity, and stay vigilant.

The Developer introduced “automated filtering systems” that monitor and review both text-chat as well as account names, and announced that as a result 500,000 accounts have been banned and 300,000 more have been re-named. The Call of Duty team stated that the implementation of such filtering systems resulted in seeing “more than [a] 55% drop in the number of offensive username and clan tags reports from our players, year-over-year, in the month of August alone in Call of Duty: Warzone.”

The anti-toxicity upgrade includes new features for in-game reporting including an optional “dialog box” that allow players to communicate more about the situation, as well as more tools to help report offensive or inappropriate behavior. Players found to engage in offensive voice chat by the moderation team are also muted the use from all in-game voice chat. Activision explained:

“We know addressing toxicity requires a 24/7 sustained effort. Since our last Call of Duty® community update, our enforcement and anti-toxicity teams have continued to progress, including scrubbing our global player database to remove toxic users.”

@B100DpR1NC3$$ does it all: Virtually beheading dragons and monitoring speech.

Although Activision’s efforts to reduce overall gamer-toxicity have proved to be seemingly successful, the true credit should be given to the players that reported misusers. Activision has repeatedly credited their so-called “enforcement and anti-toxicity teams,” effectively creating a glare over the fact that these teams, aren’t  exactly team-players. These teams instead rely on the leg work of in-game reports by actively-playing gamers, and artificial intelligence. As it turns out, the anti-toxicity team doesn’t even play the game. The team, as acknowledged by Activision, merely review reports that have already been submitted by game players.

exactly team-players. These teams instead rely on the leg work of in-game reports by actively-playing gamers, and artificial intelligence. As it turns out, the anti-toxicity team doesn’t even play the game. The team, as acknowledged by Activision, merely review reports that have already been submitted by game players.

Rather than actively dropping-in on live games to monitor and view the live talking and chat functions as they are in use, players themselves are required to do the monitoring, for them. Once players take the time to independently submit and report other users, only then will the “enforcement and anti-toxicity teams” review the report. Effectively, instead of a true monitoring system, inappropriate and non-conforming gamers will only ever be banned if someone else cares enough to report them.

LOSING THE MEANING OF VIDEO ‘GAME‘

So, going back to video games being protected as a medium of expression because they communicate ideas and social messages….. How can video games be considered a “medium of expression” to “communicate ideas,” yet evade any real monitoring of the expression within? If video games are to be considered in the boat of “books, plays, and movies” deserving of the protection of freedom of speech and expression, then it’s time for Developers and Software companies to do the leg work.

Communications between video game players are protected by the First Amendment, the same as posts by users on Facebook. Yet in society, video games are not thought of as a ‘way to communicate with someone’, the way that Facebook is, but rather as a game to play for entertainment. The reality, however, is that video games are no longer merely just games. With the rise in technology and incorporation of communication tools, video games are now a platform for toxic communication. Developers lack pressure or incentive to actually monitor the content and speech of video game players to one another, and evade further attention by publishing standards and mediocre efforts. Although Activision states that the new system “allows our moderation teams to restrict player features in response to confirmed player reports,” it’s up to players to start the process by taking the time to report in the first place. After a report is confirmed, only then, will the anti-toxicity get on their feet.

recognizes choreography as a protected form of creative expression, in order to qualify as copyrightable, the choreographic work must conform to the following elements: (1) it is an original work of authorship, (2) it is an expression as opposed to an idea, and (3) it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression. In addition, the Supreme Court has

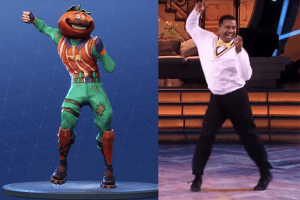

recognizes choreography as a protected form of creative expression, in order to qualify as copyrightable, the choreographic work must conform to the following elements: (1) it is an original work of authorship, (2) it is an expression as opposed to an idea, and (3) it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression. In addition, the Supreme Court has  Office. Registration is deemed to be “made” only when “the Register has registered a copyright after examining a properly filed application.” In an attempt to salvage his claim, Mr. Ribeiro proceeded to the Office but nonetheless left emptied handed. In reviewing the application, the Office refused to grant Mr. Ribeiro a copyright because the Carlton did not rise to the level of choreography since it was a simple routine made up of just three dance steps. Likewise,

Office. Registration is deemed to be “made” only when “the Register has registered a copyright after examining a properly filed application.” In an attempt to salvage his claim, Mr. Ribeiro proceeded to the Office but nonetheless left emptied handed. In reviewing the application, the Office refused to grant Mr. Ribeiro a copyright because the Carlton did not rise to the level of choreography since it was a simple routine made up of just three dance steps. Likewise,  secured a copyright for his choreographic work. Holding that golden ticket, Hanagami argued that Epic Games did not credit or seek his consent to use, display, reproduce, sell or create derivative work based on his registered choreography.

secured a copyright for his choreographic work. Holding that golden ticket, Hanagami argued that Epic Games did not credit or seek his consent to use, display, reproduce, sell or create derivative work based on his registered choreography.