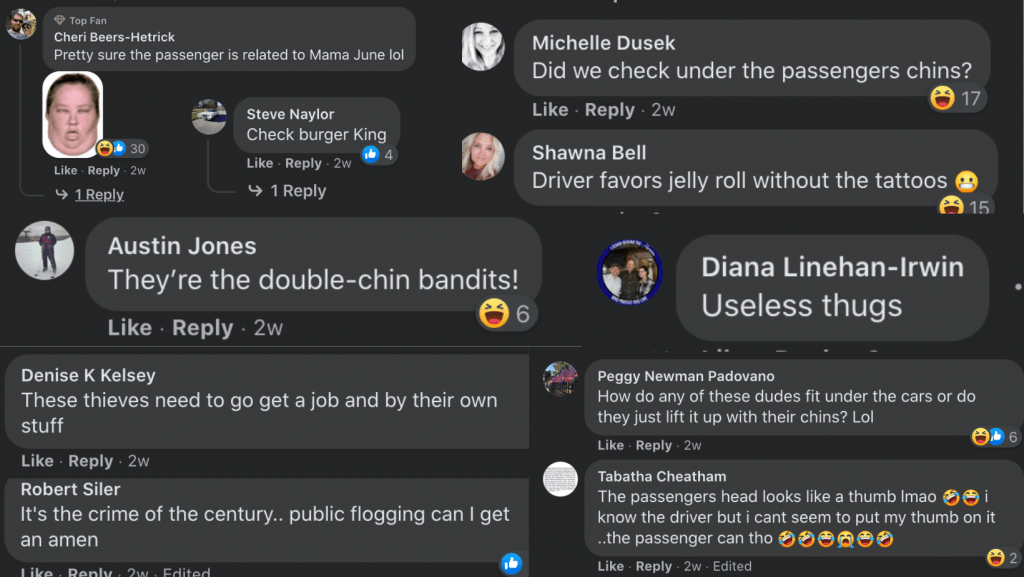

This article is in response to “Is Cyberbullying the Newest Form of Police Brutality?” which discussed law enforcement’s use of social media to apprehend people. The article provided a provocative topic, as seen by the number of comments.

I believe that discussion is healthy for society; people are entitled to their feelings and to express their beliefs. Each person has their own unique life experiences that provide a basis for their beliefs and perspectives on issues. I enjoy discussing a topic with someone because I learn about their experiences and new facts that broaden my knowledge. Developing new relationships and connections is so important. Relationships and new knowledge may change perspectives or at least add to understanding each other better. So, I ask readers to join the discussion.

My perspectives were shaped in many ways. I grew up hearing Paul Harvey’s radio broadcast “The Rest of the Story.” His radio segment provided more information on a topic than the brief news headline may have provided. He did not imply that the original story was inaccurate, just that other aspects were not covered. In his memory, I will attempt to do the same by providing you with more information on law enforcement’s use of social media.

“Is Cyberbullying the Newest Form of Police Brutality?”

The article title served its purpose by grabbing our attention. Neither cyberbullying or police brutality are acceptable. Cyberbullying is typically envisioned as teenage bullying taking place over the internet. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services states that “Cyberbullying includes sending, posting, or sharing negative, harmful, false, or mean content about someone else. It can include sharing personal or private information about someone else causing embarrassment or humiliation”. Similarly, police brutality occurs when law enforcement (“LE”) officers use illegal and excessive force in a situation that is unreasonable, potentially resulting in a civil rights violation or a criminal prosecution.

While the article is accurate that 76% of the surveyed police departments use social media for crime-solving tips, the rest of the story is that more departments use social media for other purposes. 91% notified the public regarding safety concerns. 89% use the technology for community outreach and citizen engagement, 86% use it for public relations and reputation management. Broad restrictions should not be implemented, which would negate all the positive community interactions increasing transparency.

Transparency

In an era where the public is demanding more transparency from LE agencies across the country, how is the disclosure of the public’s information held by the government considered “Cyberbullying” or “Police Brutality”? Local, state, and federal governments are subject to Freedom of Information Act laws requiring agencies to provide information to the public on their websites or release documents within days of requests or face civil liability.

New Jersey Open Public Records

While the New Jersey Supreme Court has not decided if arrest photographs are public, the New Jersey Government Records Council (“GRC”) has decided in Melton v. City of Camden, GRC 2011-233 (2013) that arrest photographs are not public records under NJ Open Public Records Act (“OPRA”) because of Governor Whitmer’s Executive Order 69 which exempts fingerprint cards, plates and photographs and similar criminal investigation records from public disclosure. It should be noted that GRC decisions are not precedential and therefore not binding on any court.

However, under OPRA, specifically 47:1A-3 Access to Records of Investigation in Progress, specific arrest information is public information and must be disclosed to the public within 24 hours of a request to include the:

- Date, time, location, type of crime, and type of weapon,

- Defendant’s name, age, residence, occupation, marital status, and similar background information.

- Identity of the complaining party,

- Text of any charges or indictment unless sealed,

- Identity of the investigating and arresting officer and agency and the length of the investigation,

- Time, location, and the arrest circumstances (resistance, pursuit, use of weapons),

- Bail information.

For years, even before Melton, I believed that an arrestee’s photograph should not be released to the public. As a police chief, I refused numerous media requests for arrestee photographs protecting their rights and believing in innocence until proven guilty. Even though they have been arrested, the arrestee has not received due process in court.

New York’s Open Public Records

In New York under the Freedom of Information Law (“FOIL”), Public Officers Law, Article 6, §89(2)(b)(viii) (General provisions relating to access to records; certain cases) The disclosure of LE arrest photographs would constitute an unwarranted invasion of an individual’s personal privacy unless the public release would serve a specific LE purpose and the disclosure is not prohibited by law.

California’s Open Public Records

Under the California Public Records Act (CPRA) a person has the statutory right to be provided or inspect public records, unless a record is exempt from disclosure. Arrest photographs are inclusive in arrest records along with other personal information, including the suspect’s full name, date of birth, sex, physical characteristics, occupation, time of arrest, charges, bail information, any outstanding warrants, and parole or probation holds.

Therefore under New York and California law, the blanket posting of arrest photographs is already prohibited.

Safety and Public Information

Recently in Ams. for Prosperity Found. V. Bonta, the compelled donor disclosure case, while invalidating the law on First Amendment grounds, Justice Alito’s concurring opinion briefly addressed the parties personal safety concerns that supporters were subjected to bomb threats, protests, stalking, and physical violence. He cited Doe v Reed which upheld disclosures containing home addresses under Washington’s Public Records Act despite the growing risks by anyone accessing the information with a computer.

Satisfied Warrant

I am not condoning Manhattan Beach Police Department’s error of posting information on a satisfied warrant along with a photograph on their “Wanted Wednesday” in 2020. However, the disclosed information may have been public information under CPRA then and even now. On July 23, 2021, Governor Newsom signed a law amending Section 13665 of the CPRA prohibiting LE agencies from posting photographs of an arrestee accused of a non-violent crime on social media unless:

- The suspect is a fugitive or an imminent threat, and disseminating the arrestee’s image will assist in the apprehension.

- There is an exigent circumstance and an urgent LE interest.

- A judge orders the release or dissemination of the suspect’s image based on a finding that the release or dissemination is in furtherance of a legitimate LE interest.

The critical error was that the posting stated the warrant was active when it was not. A civil remedy exists and was used by the party to reach a settlement for damages. Additionally, it could be argued that the agency’s actions were not the proximate cause when vigilantes caused harm.

Scope of Influence

LE’s reliance on the public’s help did not start with social media or internet websites. The article pointed out that “Wanted Wednesday” had a mostly local following of 13,600. This raised the question if there is much of a difference between the famous “Wanted Posters” from the wild west or the “Top 10 Most Wanted” posters the Federal Bureau of Investigations (“FBI”) used to distribute to Post Offices, police stations and businesses to locate fugitives. It can be argued that this exposure was strictly localized. However, the weekly TV show America’s Most Wanted, made famous by John Walsh, aired from 1988 to 2013, highlighting fugitive cases nationally. The show claims it helped capture over 1000 criminals through their tip-line. However, national media publicity can be counter-productive by generating so many false leads that obscure credible leads.

The FBI website contains pages for Wanted People, Missing People, and Seeking Information on crimes. “CAPTURED” labels are added to photographs showing the results of the agency’s efforts. Local LE agencies should follow FBI practices. I would agree with the article that social media and websites should be updated; however, I don’t agree that the information must be removed because it is available elsewhere on the internet.

Time

Vernon Gebeth, the leading police homicide investigation instructor, believes time is an investigator’s worst enemy. Eighty-five percent of abducted children are killed within the first five hours. Almost all are killed within the first twenty-four hours. Time is also critical because, for each hour that passed, the distance a suspect’s vehicle can travel expands by seventy-five miles in either direction. In five hours, the area can become larger than 17,000 square miles. Like Amber Alerts, social media can be used to quickly transmit information to people across the country in time-sensitive cases.

Vernon Gebeth, the leading police homicide investigation instructor, believes time is an investigator’s worst enemy. Eighty-five percent of abducted children are killed within the first five hours. Almost all are killed within the first twenty-four hours. Time is also critical because, for each hour that passed, the distance a suspect’s vehicle can travel expands by seventy-five miles in either direction. In five hours, the area can become larger than 17,000 square miles. Like Amber Alerts, social media can be used to quickly transmit information to people across the country in time-sensitive cases.

Live-Streaming Drunk Driving Leads to an Arrest

When Whitney Beall, a Florida woman, used a live streaming app to show her drinking at a bar then getting into her vehicle. The public dialed 911, and a tech-savvy officer opened the app, determined her location, and pulled her over. She was arrested after failing a DWI sobriety test. After pleading guilty to driving under the influence, she was sentenced to 10 days of weekend work release, 150 hours of community service, probation, and a license suspension. In 2019 10,142 lives were lost to alcohol impaired driving crashes.

Family Advocating

Social media is not limited to LE. It also provides a platform for victim’s families to keep attention on their cases. The father of a seventeen-year-old created a series of Facebook Live videos about a 2011 murder resulting in the arrest of Charles Garron. He was to a fifty-year prison term.

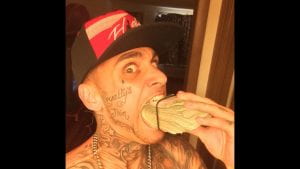

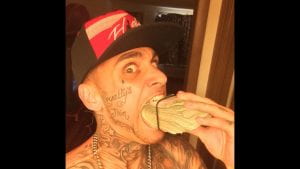

Instagram Selfies with Drugs, Money and Stolen Guns

Police in Palm Beach County charged a nineteen-year-old man with 142 felony charges, including possession of a weapon by a convicted felon, while investigating burglaries and jewel thefts in senior citizen communities. An officer found his Instagram account with incriminating photographs. A search warrant was executed, seizing stolen firearms and $250,000 in stolen property from over forty burglaries.

Bank Robbery Selfies

Police received a tip and located a social media posting by John E. Mogan II of himself with wads of cash in 2015. He was charged with robbing an Ashville, Ohio bank. He pled guilty and was sentenced to three years in prison. According to news reports, Morgan previously served prison time for another bank robbery.

Police received a tip and located a social media posting by John E. Mogan II of himself with wads of cash in 2015. He was charged with robbing an Ashville, Ohio bank. He pled guilty and was sentenced to three years in prison. According to news reports, Morgan previously served prison time for another bank robbery.

Food Post Becomes the Smoking Gun

LE used Instagram to identify an ID thief who posted photographs of his dinner at a high-end steakhouse with a confidential informant (“CI”). The man who claimed he had 700,000 stolen identities and provided the CI a flash drive of stolen identities. The agents linked the flash drive to a “Troy Maye,” who the CI identified from Maye’s profile photograph. Authorities executed a search warrant on his residence and located flash drives containing the personal identifying information of thousands of ID theft victims. Nathaniel Troy Maye, a 44-year-old New York resident, was sentenced to sixty-six months in federal prison after pleading guilty to aggravated identity theft.

Wanted Man Turns Himself in After Facebook Challenge With Donuts

A person started trolling Redford Township Police during a Facebook Live community update. It was determined that he was a 21-year-old wanted for a probation violation for leaving the scene of a DWI collision. When asked to turn himself in, he challenged the PD to get 1000 shares and he would bring in donuts. The PD took the challenge. It went viral and within an hour reached that mark acquiring over 4000 shares. He kept his word and appeared with a dozen donuts. He faced 39 days in jail and had other outstanding warrants.

The examples in this article were readily available on the internet and on multiple news websites, along with photographs.

Under state Freedom of Information Laws, the public has a statutory right to know what enforcement actions LE is taking. Likewise, the media exercises their First Amendment rights to information daily across the country when publishing news. Cyber journalists are entitled to the same information when publishing news on the internet and social media. Traditional news organizations have adapted to online news to keep a share of the news market. LE agencies now live stream agency press conferences to communicating directly with the communities they serve.

Therefore the positive use of social media by LE should not be thrown out like bathwater when legal remedies exist when damages are caused.

“And now you know…the rest of the story.”

Vernon Gebeth, the leading police homicide investigation instructor, believes time is an investigator’s worst enemy. Eighty-five percent of abducted children are killed within the first five hours. Almost all are killed within the first twenty-four hours. Time is also critical because, for each hour that passed, the distance a suspect’s vehicle can travel expands by seventy-five miles in either direction. In five hours, the area can become larger than 17,000 square miles. Like Amber Alerts, social media can be used to quickly transmit information to people across the country in time-sensitive cases.

Vernon Gebeth, the leading police homicide investigation instructor, believes time is an investigator’s worst enemy. Eighty-five percent of abducted children are killed within the first five hours. Almost all are killed within the first twenty-four hours. Time is also critical because, for each hour that passed, the distance a suspect’s vehicle can travel expands by seventy-five miles in either direction. In five hours, the area can become larger than 17,000 square miles. Like Amber Alerts, social media can be used to quickly transmit information to people across the country in time-sensitive cases.

Police received a tip and located a social media posting by John E. Mogan II of himself with wads of cash in 2015. He was charged with robbing an Ashville, Ohio bank. He pled guilty and was sentenced to three years in prison. According to news reports, Morgan previously served prison time for another bank robbery.

Police received a tip and located a social media posting by John E. Mogan II of himself with wads of cash in 2015. He was charged with robbing an Ashville, Ohio bank. He pled guilty and was sentenced to three years in prison. According to news reports, Morgan previously served prison time for another bank robbery.