It’s probably not best to “joke” around with someone seeking legal advice about how to get away with murder. Even less so doing it on social media where tone infamously, is not always easily construed. Alas, that is what happened recently in January 2021, in the case In re Sitton out of Tennessee.

Let’s lay out the facts of the case first. Mr. Sitton is an attorney who has been practicing for almost 25 years. He has a Facebook page in which he labels himself as an attorney. A Facebook “friend” of his, named Lauren Houston had posted a publicly viewable question, asking about the legality of carrying a gun in her car in the state of Tennessee. The reason for the inquiry was because she had been involved in a toxic relationship with her ex-boyfriend, who was also the father of her child. As Mr. Sitton had become aware of her allegations of abuse, harassment, violations of child custody arrangement, and requests for orders of protection against the ex, he decided to comment on the post and offer some advice to Ms. Houston. The following was Mr. Sitton’s response to her question:

“I have a carry permit Lauren. The problem is that if you pull your gun, you must use it. I am afraid that, with your volatile relationship with your baby’s daddy, you will kill your ex your son’s father. Better to get a taser or a canister of tear gas. Effective but not deadly. If you get a shot gun, fill the first couple rounds with rock salt, the second couple with bird shot, then load for bear.

If you want to kill him, then lure him into your house and claim he broke in with intent to do you bodily harm and that you feared for your life. Even with the new stand your ground law, the castle doctrine is a far safer basis for use of deadly force.”

Ms. Houston then replied to Mr. Sitton, “I wish he would try.” Mr. Sitton then replied again, “As a lawyer, I advise you to keep mum about this if you are remotely serious. Delete this thread and keep quiet. Your defense is that you are afraid for your life revenge or premeditation of any sort will be used against you at trial.” Ms. Houston then subsequently deleted the post, following the advice of Mr. Sitton.

Ms. Houston’s ex-boyfriend eventually found out about the post, including Mr. Sitton’s comments and passed screenshots of it to the Attorney General of Shelby County who then sent them to the Tennessee’s Board of Professional Responsibility (“Board”). In August 2018, the Board filed a petition for discipline against him. The petition alleged Mr. Sitton violated Rule of Professional Conduct by “counseling Ms. Houston about how to engage in criminal conduct in a manner that would minimize the likelihood of arrest or conviction.”

Mr. Sitton admitted most of the basic facts but attempted to claim his comments were taken out of context. One of the things Mr. Sitton has admitted to during the Board’s hearing on this matter was that he identified himself as a lawyer in his Facebook posts and intended to give Ms. Houston legal advice and information. He noted Ms. Houston engaged with him on Facebook about his legal advice, and he felt she “appreciated that he was helping her understand the laws of the State of Tennessee.” Mr. Sitton went on to claim his only intent in posting the Facebook comments was to convince Ms. Houston not to carry a gun in her car. He maintained that his Facebook posts about using the protection of the “castle doctrine” to lure Mr. Henderson into Ms. Houston’s home to kill him were “sarcasm” or “dark humor.”

The hearing panel found Mr. Sitton’s claim that his “castle doctrine” comments were “sarcasm” or “dark humor” to be unpersuasive, noting that this depiction was challenged by his own testimony and Ms. Houston’s posts. The panel instead came to the determination that Mr. Sitton intended to give Ms. Houston legal advice about a legally “safer basis for use of deadly force.” Pointing out that the Facebook comments were made in a “publicly posted conversation,” the hearing panel found that “a reasonable person reading these comments certainly would not and could not perceive them to be ‘sarcasm’ or ‘dark humor. They also noted Mr. Sitton lacked any remorse for his actions. It acknowledged that he conceded his Facebook posts were “intemperate” and “foolish,” but it also pointed out that he maintained, “I don’t think what I told her was wrong.”

The Board decided to only suspend Mr. Sitton for 60 days. However, the Supreme Court of Tennessee reviews all punishments once the Board submits a proposed order of enforcement against an attorney to ensure the punishment is fair and uniform to similar circumstances/punishments throughout the state. The Supreme Court found the 60-day suspension to be insufficient and increased Mr. Sitton’s suspension to 1-year active suspension and 3 years on probation.

Really? While I’m certainly glad the Tennessee Supreme Court increased his suspension, I still think one year is dramatically too short. How do you allow an attorney who has been practicing for nearly 30 years to only serve a 1-year suspension for instructing someone on how to get away with murder? Especially when both the court and hearing panel found no mitigating factors, that a reasonable person would not interpret his comments to have been dark humor and that it was to be interpreted as real legal advice? What’s even more mind boggling is that the court found Mr. Sitton violated ABA Standards 5.1 (Failure to Maintain Personal Integrity) and 6.1 (False Statements, Fraud, and Misrepresentation), but then twisted their opinion and essentially said there was no real area in which Mr. Sitton’s actions neatly fall into within those two rules and therefore that is why they are only giving a 1-year suspension. The thing is, that is simply inaccurate for the sentencing guidelines (which the court included in their opinion) for violations of 5.1 and 6.1, it is abundantly obvious that Mr. Sitton’s actions do fall into them clearly, so it is a mystery as to how the court found otherwise.

If you were the judge ruling on this disciplinary case, what sentencing would you have handed down?

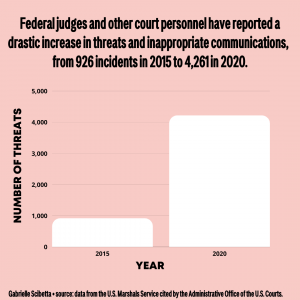

Thankfully, not all threats result in successful or fatal attacks – but the rise of intimidation tactics and inappropriate communications with federal judges and other court personnel has quadrupled since 2015.

Thankfully, not all threats result in successful or fatal attacks – but the rise of intimidation tactics and inappropriate communications with federal judges and other court personnel has quadrupled since 2015.

There are some social media challenges that are harmless including the 2014 Ice Bucket Challenge, which earned millions of dollars for ALS research.

There are some social media challenges that are harmless including the 2014 Ice Bucket Challenge, which earned millions of dollars for ALS research.