In 1996 Congress passed what is known as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA) which provides immunity to website publishers for third-party content posted on their websites. The CDA holds that “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” This Act passed in 1996, was created in a different time and era, one that could hardly envision how fast the internet would grow in the coming years. In 1996, social media for instance consisted of a little-known social media website called Bolt, the idea of a global world wide web, was still very much in its infancy. The internet was still largely based on dial-up technology, and the government was looking to expand the reach of the internet. This Act is what laid the foundation for the explosion of Social Media, E-commerce, and a society that has grown tethered to the internet.

The advent of Smart-Phones in the late 2000s, coupled with the CDA, set the stage for a society that is constantly tethered to the internet and has allowed companies like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Amazon to carve out niches within our now globally integrated society. Facebook alone in the 2nd quarter of 2021 has averaged over 1.9 billion daily users.

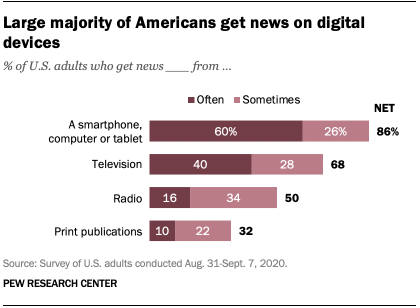

Recent studs conducted by the Pew Research Center show that “[m]ore than eight in ten Americans get news from digital services”

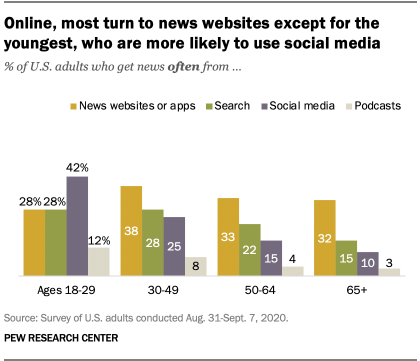

While older members of society still rely on news media online, the younger generation, namely those 18-29 years of age, receive their news via social media.

The role Social Media plays in the lives of the younger generation needs to be recognized. Social Media has grown at a far greater rate than anyone could imagine. Currently, Social Media operates under its modus operandi, completely free of government interference due to its classification as a private entity, and its protection under Section 230.

Throughout the 20th century when Television News Media dominated the scenes, laws were put into effect to ensure that television and radio broadcasters would be monitored by both the courts and government regulatory commissions. For example, “[t]o maintain a license, stations are required to meet a number of criteria. The equal-time rule, for instance, states that registered candidates running for office must be given equal opportunities for airtime and advertisements at non-cable television and radio stations beginning forty-five days before a primary election and sixty days before a general election.”

What these laws and regulations were put in place for was to ensure that the public interest in broadcasting was protected. To give substance to the public interest standard, Congress has from time to time enacted requirements for what constitutes the public interest in broadcasting. But Congress also gave the FCC broad discretion to formulate and revise the meaning of broadcasters’ public interest obligations as circumstances changed.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) authority is constrained by the first amendment but acts as an intermediary that can intervene to correct perceived inadequacies in overall industry performance, but it cannot trample on the broad editorial discretion of licensees. The Supreme Court has continuously upheld the public trustee model of broadcast regulation as constitutional. The criticisms of regulating social media center on the notion that they are purely private entities that do not fall under the purviews of the government, and yet these same issues are what presented themselves in the precedent-setting case of Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. Federal Communications Commission (1969. In this case, the court held that “rights of the listeners to information should prevail over those of the broadcasters.” The Court’s holding centered on the public right to information over the rights of a broadcast company to choose what it will share, this is exactly what is at issue today when we look at companies such as Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat censuring political figures who post views that they feel may be inciteful of anger or violence.

In essence, what these organizations are doing is keeping information and views from the attention of the present-day viewer. The vessel for the information has changed, it is no longer found in television or radio but primarily through social media. Currently, television and broadcast media are restricted by Section 315(a) of the Communications Act and Section 73.1941 of the Commission’s rules which “require that if a station allows a legally qualified candidate for any public office to use its facilities (i.e., make a positive identifiable appearance on the air for at least four seconds), it must give equal opportunities to all other candidates for that office to also use the station.” This is a restriction that is nowhere to be found for Social Media organizations.

This is not meant to argue for one side or the other but merely to point out that there is a political discourse being stifled by these social media entities, that have shrouded themselves in the veils of a private entity. However, what these companies fail to mention is just how political they truly are. For instance, Facebook proclaims itself to be an unbiased source for all parties, and yet what it fails to mention is that currently, Facebook employs one of the largest lobbyist groups in Washington D.C. Four Facebooks lobbyist have worked directly in the office of House Speaker Pelosi. Pelosi herself has a very direct connection to Facebook, she and her husband own between $550,000 to over $1,000,000 in Facebook stock. None of this is illegal, however, it raises the question of just how unbiased is Facebook.

If the largest source of news for the coming generation is not television, radio, or news publications themselves, but rather Social Media such as Facebook, then how much power should they be allowed to wield without there being some form of regulation? The question being presented here is not a new one, but rather the same question asked in 1969, simply phrased differently. How much information is a citizen entitled to, and at what point does access to that information outweigh the rights of the organization to exercise its editorial discretion? I believe that the answer to that question is the same now as it was in 1969 and that the government ought to take steps similar to those taken with radio and television. What this looks like is ensuring that through Social Media, that the public has access to a significant amount of information on public issues so that its members can make rational political decisions. At the end of that day that it was at stake, the public’s ability to make rational political decisions.

These large Social Media conglomerates such as Facebook and Twitter have long outgrown their place as a private entity, they have grown into a public medium that has tethered itself to the realities of billions of people. Certain aspects of it need to be regulated, mainly those that interfere with the Public Interest, there are ways to regulate this without interfering with the overall First Amendment right of Free Speech for all Americans. Where however Social Media blends being a private forum for all people to express their ideas under firmly stated “terms and conditions”, and being an entity that strays into the political field whether it be by censoring heads of state, or by hiring over $50,000,000 worth of lobbyist in Washington D.C, there need to be some regulations put into place that draw the line that ensures the public still maintains the ability to make rational political decisions. Rational decisions that are not influenced by anyone organization. The time to address this issue is now when there is still a middle ground on how people receive their news and formulate opinions.