When a judge renders a legal decision, they hardly anticipate that their commitment to serving the public could make themselves or their family a target for violence. Rather than undergo the appeals process when an unfavorable verdict is reached, disgruntled civilians are threatening and even attacking the presiding judges and their families – placing them in fear of their lives.

Earlier this month, the federal judiciary introduced legislation which aims to safeguard the personal information of judges and their immediate family members within federal databases and restrict data aggregators from reselling that information. The Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts announced their support for the Daniel Anderl Judicial Security and Privacy Act of 2021, named for the late son of Judge Esther Salas of the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey.

The bill comes in response to the tragedy that occurred on July 19, 2020, when an angered attorney disguised as a FedEx delivery driver showed up at the Salas’ home and opened fire. In attempting to assassinate Salas, the gunman shot and killed her 20-year-old son, Daniel, and wounded her husband, attorney Mark A. Anderl. A day after the racially motivated attack, the gunman, Roy Den Hollander, was found dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

The Manhattan attorney and self-proclaimed “anti-feminist” appeared in Salas’ courtroom months prior to the attack. According to the FBI, Hollander had detailed information on Salas and her family, in addition to several other targets on his radar. An autobiography published to Hollander’s personal website revealed anti-feminist ideology and his extreme displeasure with Salas, including the following posts:

- “If she ruled draft registration unconstitutional, the Feminists who believed females deserved preferential treatment would criticize her. If she ruled that it did not violate the Constitution, then those Feminists who advocate for equal treatment would criticize her. Either way it was lose-lose for Salas unless someone took the risk of leading the way”

- “Female judges didn’t bother me as long as they were middle age or older black ladies…Latinas, however, were usually a problem — driven by an inferiority complex.”

- In another passage, he wrote that Salas was a “lazy and incompetent Latina judge appointed by Obama.”

- He criticized Salas’ resume, writing that “affirmative action got her into and through college and law school,” and that her one accomplishment was “high school cheerleader.”

In a news video two-weeks after the incident, Salas shared that “unfortunately, for my family, the threat was real, and the free flow of information from the internet allowed this sick and depraved human being to find all our personal information and target us. In my case, the monster knew where I lived and what church we attended and had a complete dossier on me and my family.” Since her sons’ killing, Judge Salas has been personally advocating for stronger protections to ensure that judges are able to render decisions without fear of reprisal or retribution – not only for safety purposes, but because our democracy depends on an independent judiciary.

***

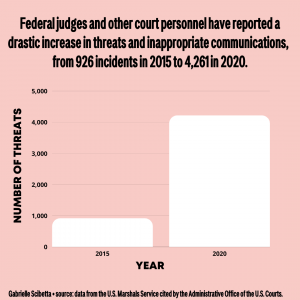

Sadly, Judge Salas is not alone in the terrible misfortune that occurred last year. Judges are regularly threatened and harassed, specifically after high-profile legal battles with increased media attention – increasing 400% over the past five years. Four federal judges have been murdered since 1979. District Judge John Wood was assassinated outside his home in 1979 by hitman Charles Harrelson. In 1988, U.S. District Judge Richard Daronco was shot and killed in the front yard of his Pelham, New York, home. In 1989, Circuit Judge Robert Vance was killed when he opened a mail bomb sent to his home. District Judge John Roll was shot in the back and killed in 2011 at an event for Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, who was also shot and injured. (https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/federal-judiciary-supports-legislation-to-prevent-access-to-judges-information)

Thankfully, not all threats result in successful or fatal attacks – but the rise of intimidation tactics and inappropriate communications with federal judges and other court personnel has quadrupled since 2015.

Thankfully, not all threats result in successful or fatal attacks – but the rise of intimidation tactics and inappropriate communications with federal judges and other court personnel has quadrupled since 2015.

U.S. District Judge Julie Kocurek was shot in front of her family in 2015. She miraculously survived but sustained severe injuries and underwent dozens of surgeries. The attempted assassin was a plaintiff before her court and had been tracking the judges’ whereabouts. Former Texas Federal Judge Liz Lang Miers attributes the attacks to someone misperceiving a ruling and acting irrationally “as opposed to understanding the justice system.”

In 2017, Seattle federal Judge James Robart received more than 42,000 letters, emails and calls, including more than 100 death threats, after he temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s travel ban that barred people from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen from entering the U.S. for 90 days. (https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/attack-judge-salas-family-highlights-concerns-over-judicial-safety-n1234476)

The Internet, notably social media, has amplified the criticisms that citizens have with the judicial system. Rather than listening to and comprehending the entirety of a court ruling, an individual can fire off a tweet or post at the click of a button, spreading that inaccurate information worldwide. Before long, hundreds of thousands of people have seen that communication and are quick to draw conclusions despite not understanding the merits of the legal opinion. Misinformation, or misleading information or arguments, often aiming to influence a subset of the public, spreads rapidly. Data indicates that articles containing misinformation were among the most viral content, with “falsehoods diffusing significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information.” (https://voxeu.org/article/misinformation-social-media).

***

Since 1789, federal judges have been entitled to home and court security systems and protections by the U.S. Marshals service – however the threats and attacks continue to prevail.

As elected public servants, judges’ information is made publicly available and easily accessible through a simple Google search. The Daniel Anderl Judicial Security and Privacy Act would shield the information of federal judges and their families, including home addresses, Social Security numbers, contact information, tax records, marital and birth records, vehicle information, photos of their vehicle and home, and the name of the schools and employers of immediate family members.

Many officials are onboard with the proposed legislation. Senator Menendez, who recommended Judge Salas to President Barack Obama for appointment to the federal bench, reveals that “the threats against our federal judiciary are real and they are on the rise. We must give the U.S. Marshals and other agencies charged with guarding our courts the resources and tools they need to protect our judges and their families. I made a personal commitment to Judge Salas that I would put forth legislation to better protect the men and women who sit on our federal judiciary, to ensure their independence in the face of increased personal threats on judges and help prevent this unthinkable tragedy from ever happening again to anyone else.” Moreover, Rep. Fitzpatrick noted that, “in order to bolster our ability to protect our federal judges and their families, we need to safeguard the personally identifiable information of our judges and optimize our nation’s personal data sharing and privacy practices.”

Additionally, the bill is supported by the New Jersey State Bar Association, National Association of Attorneys General, Judicial Conference of the United States, Federal Magistrate Judges Association, American Bar Association (ABA), Dominican Bar Association, New York Intellectual Property Law Association, Federal Bar Council, Hispanic National Bar Association (HNBA), and Federal Judges Association.

***

In memory of Daniel Anderl, taken too soon at 20-years-young. As the only child of U.S. District Court Judge Esther Salas and defense attorney Mark Anderl, Daniel gave his life to save his parents. He was a student at Catholic University in Washington, DC. There is a plaque honoring Daniel at the entrance of the Columbus School of Law at Catholic University, as he planned to pursue a career in law. The plaque is also to serve as a reminder to young people that