Upon its launch in 2011, the mobile app known as “Snapchat” quickly gained downloads, now totaling 265 million daily active Snapchat users worldwide. Snapchat revolutionized the social media world with the introduction of filters – debuting “smart filters” to capture time, speed, and temperature in 2013, followed by “Geofilters” in August 2014 and “Discover” and “Lenses” in January 2015.

Snapchat in 2013

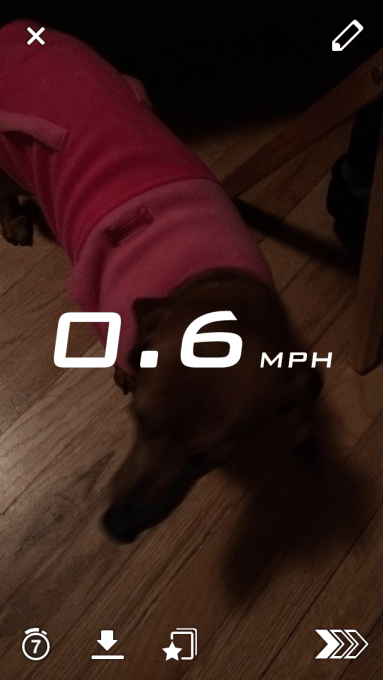

While filters can provide fun visual effects and cool color edits, the “speed filter” drew criticism early on for encouraging yet another distraction on the road for young drivers. Newly licensed teens could hardly wait to get in the driver’s seat and snap a selfie overlayed with vehicle speed in real time. The widespread belief is that users would earn a virtual trophy through the apps reward system for snapping speeds over 100 miles per hour (mph) – further fueling the recklessness.

img: The Odyssey

Concerns were raised early on regarding the dangers of the speed filter, and Snap responded by attaching a “Do Not Snap and Drive” disclaimer in 2016. Despite the company’s minimal efforts to limit the use of the feature while driving, life-threatening and fatal car accidents linked to the filter prevailed.

Studies indicate that Snapchat leads the list of apps most distracting for young drivers, and more than a third of teens surveyed admitted to Snapping while driving. The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration reports nearly 26,004 deaths due to distracted driving accidents between 2012 and 2019. By 2018, distraction-related fatalities increased by 10% – killing 2,841 people and injuring 400,000 more. Drivers under the age of 19 account for the largest proportion of distracted driving fatalities.

One of the earliest accidents involving the filter occurred in September 2015, with 18-year-old Christal McGee behind the wheel of her father’s Mercedes. McGee admitted to grabbing her phone and using the filter to see how fast she could go. The Atlanta-teen doubled the speed limit at roughly 113 mph before colliding with an Uber driver who was just beginning his night shift. As a result of the accident, the Uber driver was hospitalized for months and suffered a traumatic brain injury. He sued both McGee and Snapchat for negligence damages, alleging equal responsibility by Snapchat for the crash because they failed to delete the miles per hour filter after it was cited in similar accidents prior to the September 2015 crash.

Likewise, an incident occurred in late 2016 when 22-year-old Pablo Cortes posted a Snapchat video with the speed filter, accelerating from 82 mph to 115.6 mph. Just nine minutes later, Cortes lost control and struck a minivan – killing both himself and his 19-year-old passenger, Jolie Bartolome, as well as a mother and two of her children.

In the past, Snapchat has not faced liability for incidents arising out of the speed filter due to the Communications Decency Act (CDA). Section 230 of the CDA states that “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider” (47 U.S.C. § 230). Congress established the CDA in 1996, with the intent to better regulate pornographic material on the Internet. With the growth of social media, it serves as a powerful tool that shields tech companies and social media platforms from potential liability for content posted by their users.

However, just last month the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit unanimously held that the CDA does not shield the creators of Snapchat from claims. The lawsuit in Lemmon v. Snap arises out of an incident that occurred May of 2017, fatally wounding three young boys. The 17-year-old driver and his two buddies used the speed filter to record a high of 123 mph, just before hitting a tree at 113 mph. The parents of the deceased teens filed a lawsuit in 2019, alleging the “negligent design” of the Snap Inc. app contributed to the crash by encouraging speeding. The trial judge erroneously dismissed the case in 2020, citing the immunity social media companies enjoy under the CDA.

In departing from the district court’s decision, the Ninth Circuit applied the three-prong test set forth in Barnes v. Yahoo!, Inc. (2009) to assess whether Section 230 would apply to immunize Snap from the claims. As such, CDA immunity will shield Snap from liability only if “(1) a provider or user of an interactive computer service (2) whom a plaintiff seeks to treat, under a state law cause of action, as a publisher or speaker (3) of information provided by another information content provider.” (quoting Barnes). In thoughtfully analyzing each of the three prongs, the Court reversed the district court’s dismissal of the lawsuit and remanded it for further proceedings.

This new recognition rests on the fact that the suit is not about what someone posted to Snapchat, but rather negligence in the design of the app overall. The decision is a huge turning point in Internet law and regulation because it establishes that an internet company can be held liable for products with a defective design. Although the language of Section 230 grants broad discretion, Lemmon is a clear demonstration that Internet immunity has its limits and is not guaranteed. While the ruling is among the minority that have rejected CDA immunity to design claims against internet platforms, this radical departure from earlier decisions opens the door to future legal challenges to CDA immunity by alleging injury based on how the website’s design affected the user, rather than how the user’s content affected a third party.

Kudos to the Ninth Circuit for framing the issue in a way that circumvents Section 230. While it is imperative to retain that portion of section 230 that protects free speech, recent concerns about the law highlight its unwieldy reach. The Barnes test that you highlight appears to provide courts with an opportunity to impart justice without violating the letter of the CDC law. I will be curious to see whether these issues, which seem to allow individuals to sue ISPs successfully, will make their way to the Supreme Court.